Evolution of the U.S. Presidency

It was beneficial for the United States to have George Washington as the first president. Washington was aware his actions would be reviewed for centuries to come; he wrote that his foray into the first presidency was like "entering upon an unexplored field, enveloped on every side with clouds & darkness" [source: National Archives]. Washington had no model on which to base his actions, and every decision he made would set precedent for presidents to come.

To fully understand what a president does and how he or she does it, it's important to view a president not as an incumbent holding office for four or eight years, but as a part of a larger organism, the presidency itself. The office is a dynamic, ever-evolving thing that's molded, carved, expanded upon, battered and made different by every person who holds it. The presidency, in other words, is larger than any single president.

Advertisement

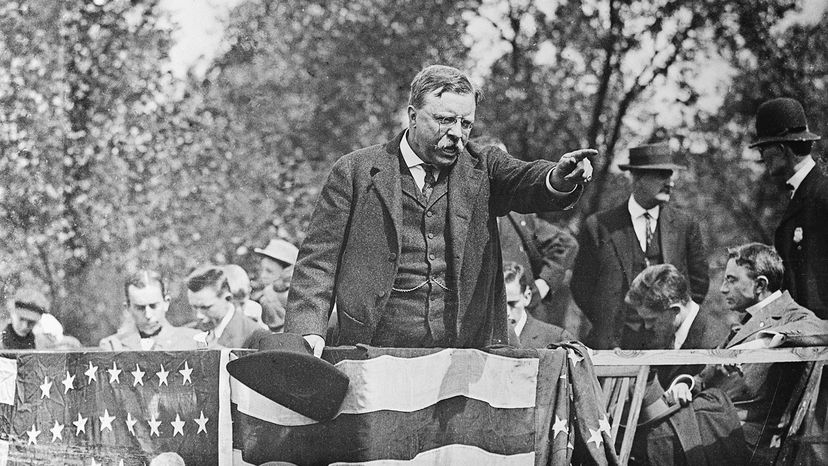

The presidency is founded on customs established by past presidents. President Washington established the president as the leader of the nation in foreign affairs and established the tradition of negotiating treaties with other nations without prior approval of Congress (confirmation of treaties now comes after). Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson established the president as the head of his or her political party. Theodore Roosevelt sharpened the inherent power of what he called the bully pulpit — the public limelight naturally afforded to every president, which can be used to gain popular support for policies.

Presidential powers and limitations also emerge from the interplay between the president and the other branches. A president can make a play for new power into uncharted territory; regardless of whether the action is upheld or struck down, a precedent has been set and the presidency molded anew. Thomas Jefferson purchased the Louisiana Territory from France without congressional consent. President George W. Bush's domestic spying policies gave immunity to telecommunication companies who'd illegally given their customers' information to the government. In cases like these, the president used his office to act, and Congress often falls in line after the fact.

The direction can also reverse. Congress perceived Richard Nixon as abusing a long-standing presidential power to impound funds appropriated for laws and programs. Previously, presidents could hold funds for administrative reasons, like accounting errors that required repair (accidentally adding a zero can really increase a fund, for example). President Nixon used the impound power to block bills he'd vetoed but Congress had overridden; with no funding, there was no legislation. In response, Congress passed the Budget and Impoundment Control Act in 1974, and the presidential power to impound appropriations was revoked.

How a presidency plays out is also largely based on the mood of Congress and the public (often created by the behavior of the president's predecessor) and the state of the nation. In times of relative national tranquility and calm, Congress is usually most powerful. Members can take a longer view and address issues that will affect future generations. But in times of crisis, such as a failing economy or war, the responsiveness and decisiveness of the presidency becomes vital. In times of crisis, presidential power is often greatly expanded. Franklin Roosevelt, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt and George W. Bush all added sweeping powers to the presidency to address wars and economic crises like the Great Depression and the war on terror.

This is how the framers of the Constitution intended it; the three branches are meant to check and balance each other.