Back in the early 1990s, most of us weren't yet savvy Internet surfers. We still got all our news from the paper rather than Web sites, and e-mail hadn't yet taken over faxes and letters in our business and personal lives. Many of us were still years away from learning about the possibilities of the Internet -- that is, if we'd heard of it at all. However, Bill Burrall, a computer instructor for Moundville Junior High School in West Virginia, was ahead of us. He'd already been steeped in the Internet world for over a decade, and was not only thoroughly familiar with it, but recognized its educational potential for students.

Using the AT&T Learning Network, a worldwide educational Internet community, Burrall and his middle school classes participated in a valuable telecommunications project where kids got the chance to correspond with other classes from around the country and around the world. After realizing the success of these projects, Burrall decided to take advantage of the same system in a new way that later put him in the national spotlight.

Advertisement

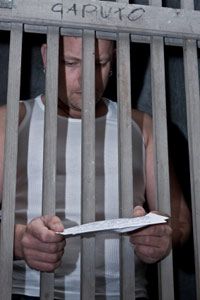

As it happened, Moundsville Junior High was situated merely a few blocks from West Virginia's State Penitentiary. Where most teachers would have found this close proximity a source of concern, Burrall saw opportunity. The school would serve as a focal point for Burrall's revolutionary prison project, which used telecommunications to connect kids from around the world to the prison's inmates. After a year of struggle to get his idea approved by the school board and eventually the governor, Burrall was finally able to launch his prison project in 1992, later known as the "Inmates and Alternatives Project."

Read the next page to find out how Burrall used telecommunications to offer students life-altering experiences.

Advertisement