A new study by researchers at the Public Policy Institute of California shows that a recent move to reduce the Golden State's prison population has had little impact on crime rates across the state. Those findings could bolster efforts to reduce overcrowding behind bars throughout the country.

"I think probably the most important takeaway is that states can look at a major change like prison realignment," says University of California, Irvine criminology professor Charis Kubrin, co-editor of the publication that included the study, "and not be worried that it's going to impact public safety in a major way."

Advertisement

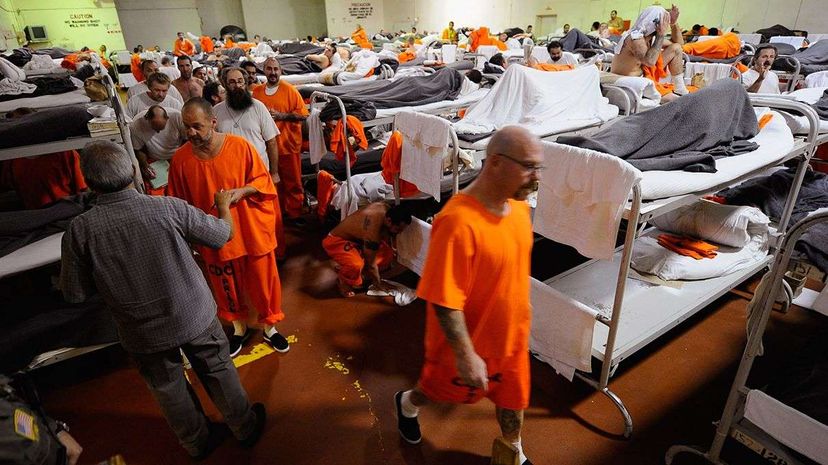

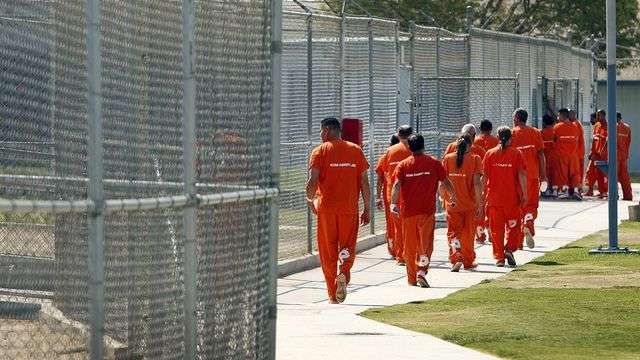

Kubrin and fellow criminology professor Carroll Serron edited a recent issue of the journal Annals of the American Academy of Political & Social Science dedicated to studying the impact of a 2011 law that trimmed the population in state-run prisons by more than 20 percent over two years. The law was a response to a U.S. Supreme Court ruling, in which the high court said the state's prisons were so overcrowded that the conditions violated prisoners' constitutional rights. In response, California legislators moved to shift 33,000 non-violent inmates from prisons to county jails, probation, into monitored home-release programs, rehab facilities and into a reformed parole system.

"We've seen no appreciable uptick in assaults, rapes or murders that can be connected to the prisoners who were released under realignment," says Kubrin. "This is not surprising, of course, because these offenders were eligible for release precisely because of the nonviolent nature of their crimes."

The research compared crime rates over time to find little or no impact on violent offenses across the state. While the data did reveal a small uptick in car thefts and other property crimes, the researchers determined that the costs of those crimes were outweighed by savings related to decarceration. The research found that while one year behind bars for one inmate prevents 1.2 auto thefts per year and saves $11,783 in crime-related costs (acknowledging the impact on the individual victim), it costs the society and California taxpayers $51,889 per year to incarcerate a prisoner — and that doesn't even account for the further cost ripple in the economy due to hardships experienced by the inmate's family.

The case for criminal justice reform is getting a whole lotta love these days. A wide variety of folks say something needs to be done about heavy-handed punishments for non-violent offenders and the prison-industrial complex that's sprung up as a result.

There are many reasons behind the idea that long stretches behind bars might not be the best way to fight lower-level crime. Prisons are expensive, overcrowded and sometimes not in the best of shape. Many relatively minor offenders taking up space behind bars are eventually going to be back on the street, and holing them up like hamsters in a cage might not necessarily help the transition into the real world.

Still, not everyone is hip to the idea of opening up the prison doors and throwing out the keys. You do the crime, you do the time, as they say. That's not to mention the notion that the most certain way to keep someone who has shown a proclivity for law breaking from doing it again is to keep him incarcerated. This recent research, however, may go a long way in tamping down fears about letting convicts out of the stripey hole at little earlier than expected.

Of course, this California experiment isn't without its critics, who say prison officials are simply shifting the burden from state budget sheets to swelling local jails. But Kubrin argues that something has to be done to combat the incarceration state.

"It's time to start thinking outside of the box and start trimming away at these crazy prison population rates," she says.

Advertisement