At the Trial

As most of us know from watching Law & Order or L.A. Law, the first thing that happens in the trial is the plaintiff's attorney's opening statement (if it is a jury trial), followed by the defendant's attorney's opening statement. The opening statement is like the preview for a movie. You'll hear the highlights of the case and evidence that will be presented and get the gist of the story.

Since evidence is usually introduced through the witnesses' testimony, the order in which the witnesses take the stand and the questions they are asked must be set up with precision. In civil cases, the plaintiff's attorney is allowed to call the defendant to the stand, as well. Attorneys can also introduce evidence (if both sides have agreed that it can be introduced) by stipulation.

Advertisement

Questioning the Witnesses

The questioning of each witness by the attorney who called that witness to the stand is called direct examination. During the direct examination, the opposing attorney can object to the question before the witness has a chance to answer it. The attorney may be objecting to the question itself or to the way the question is being asked. For example, the way the question is asked may be "leading" the witness to a specific answer. He may also object to the question because the witness's answer would be hearsay (meaning the witness doesn't know the information first-hand).

The judge decides if the attorney's objection is justified (sustained) or not justified (overruled). If the witness answers a question before the judge has a chance to say whether the question should be withdrawn, then the judge can instruct the jury to disregard the witness's answer.

Once the plaintiff's attorney has asked a witness all of the questions he has prepared, then the defendant's attorney gets an opportunity to ask questions, known as cross-examining the witness. After the defendant's cross-examination, the plaintiff can redirect more questions. These redirect questions have to relate to the information that was brought out in the original questioning. The defendant can then recross-examine, with the same restriction that these questions relate to the original questioning.

After the plaintiff's attorney has called all witnesses, the plaintiff's case rests. Then, the defendant's attorney begins calling witnesses for the defense. The same rules apply for cross-examination and redirects. When the defendant's attorney has questioned all witnesses for the defense, then the defendant's case also rests.

Burden of Proof

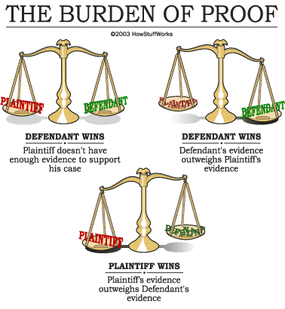

In civil cases, the plaintiff has the "burden of proof," meaning, essentially, that the plaintiff has to have greater evidence to prove his case than the defendant must have to prove his -- hence the "scales of justice." If the plaintiff's evidence isn't great enough to tip the scales, the defendant wins.

For punitive damages (in most states), the burden of proof is a step higher. There must be "clear and convincing" evidence in order to win the case. This is a middle standard of proof, falling between the "preponderance" standard of most civil cases, where one side simply has to have more evidence in its favor, and the criminal standard of "beyond a shadow of a doubt."

Closing Statements

Each attorney sums up the evidence and facts presented in the trial in their closing statements (if there is a jury). No additional information can be introduced during these statements. The plaintiff's attorney closes first, then the defendant's attorney, then the plaintiff's attorney has an opportunity to make an additional statement, usually to clarify something the opposing side said. This is called a rebuttal.

The Jury

In jury trials, the judge instructs the jury members on how they should go about deciding the case (deliberating), which party has the burden of proof, how the law should be applied, and whether they have to have a unanimous vote or not. Either the jury will select its own foreman or the judge will assign one (the jury foreman takes charge of the process). The jury then goes to a private room to discuss the facts of the case and vote on the outcome.

When the jury has voted and made its decision, the members return to the courtroom and the foreman reads the verdict.

Sometimes, the jury just can't come to a decision. This is called a deadlocked jury or a hung jury, and can lead to a mistrial. If there is a mistrial, the trial is over but no one has won. In this case, the parties have to retry the case or find some other way to find a solution. Post-trial Proceedings and Appeals

Even after the trial, there are some steps to go through. Let's say the plaintiff wins the case. The plaintiff's attorney must evaluate the costs and come up with the totals in order to formalize the judgement. The clerk of court then files a "notice of entry of judgement."

The plaintiff also has to determine how he's going to enforce the judgement. If the defendant must pay the plaintiff money, then (depending on the state) the plaintiff may have options on how to collect -- this may include garnishing wages, taking assets to cover the dollar amount, or putting a lien on property.

And, while these decisions are being made, there is always the possibility that the defendant is still trying to win the case. The defendant may try to get the judge to overturn the ruling, or request a new trial based on some problem that occurred during the trial, or appeal the case to a higher court. Remember the "motion for judgement notwithstanding verdict?" If the jury's verdict was really off-base to most reasonable people, then the judge might agree to the motion and change the verdict.

For more information on lawsuits and related topics, check out the links that follow.