A few years back, if you had tuned into a TV drama depicting a presidential election in which the wife of a former president was pitted against a brash, abrasive real estate tycoon turned reality-show host, you might have grumbled about the far-fetched imagination of the script writers. But rest assured, the strange circumstances of the 2016 general election campaign aren't totally without precedent.

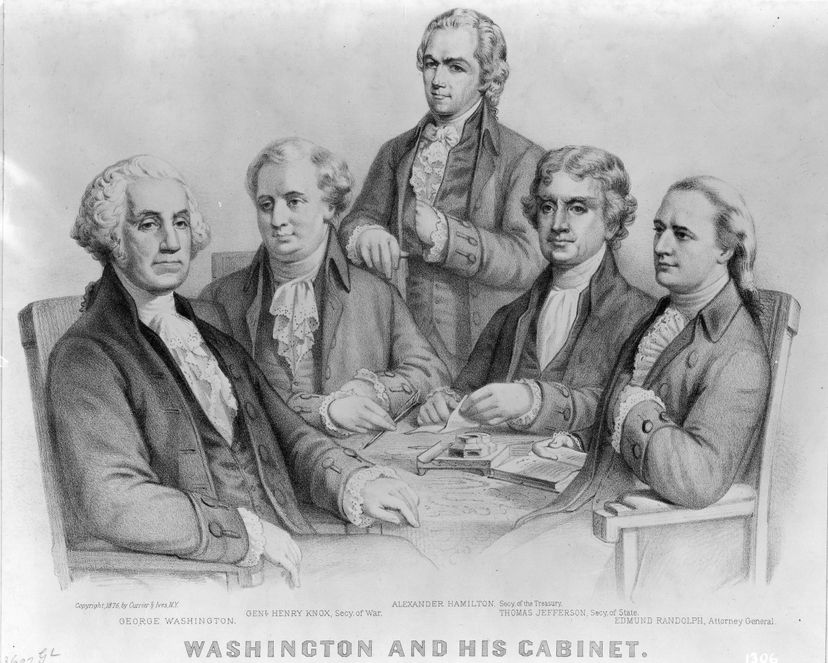

Throughout American history, presidential campaigns have seen so many seemingly unlikely — if not outright bizarre — twists that strangeness actually might be the rule, rather than the exception. There was the election of 1800, for example, in which an Electoral College tie between Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr — who happened to be both from the same Democratic-Republican political party — forced the House of Representatives to spend a week and numerous votes deciding the winner. Ultimately, their choice was influenced by a member of the rival Federalist Party, Alexander Hamilton, who didn't like either man, but preferred Jefferson as the lesser of two evils. (Burr would later kill Hamilton in a duel) [source: McLaughlin].

Advertisement

And there was the 1896 race between Republican William McKinley and Democrat William Jennings Bryan, in which Bryan roamed the country on a whistle-stop train tour, logging 18,000 miles (28,968 kilometers), while McKinley — who apparently couldn't be bothered to travel — chose to stay on his front porch in Canton, Ohio and give speeches to delegates. Amazingly, the voting public was fine with that, and McKinley won [source: Miller Center].

And these examples aren't even the strangest ones. So, without further ado, here's a list of 10 of the most bizarre moments in U.S. presidential elections.