It's a rare moment indeed that an American kid responds to the question, "What do you want to be when you grow up?" with "vice president!" Perhaps that's because the office, as historian Mark Hatfield wrote, is "the least understood, most ridiculed, and most often ignored constitutional office in the federal government" [source: Hatfield].

It makes sense; the vice presidency was originally a consolation prize given to the runner-up in the national election. State electors were asked to cast ballots for two candidates, and one of the candidates had to live outside of the elector's home state. This process assured that eventually a leader of national prominence would emerge as president; the person who came in second became vice president.

Advertisement

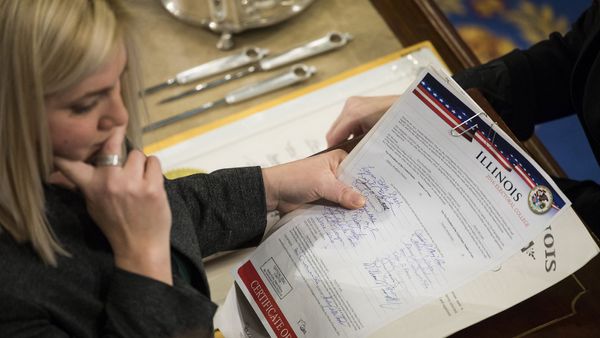

More than two centuries later, the role of vice president is little more respected among the public than it was in the beginning. But this perception is despite the contributions and efforts of a long line of seconds-in-command. Some vice presidents have gone on to fulfill the presidency, taking over after the president's death or winning a later election. Admittedly, some have done more with their position than others. The office is definitely what a vice president makes of it; the Constitution offers no guidelines for the vice president other than that the "Vice President of the United States shall be President of the Senate," but he or she can vote only as a tie breaker [source: Cornell].

But the role of the vice president has always been a potentially important one. He or she is next in line for the presidency, a "heartbeat away" from arguably the most powerful position in the world as the office of president was described during the 2008 presidential race [source: Newsday]. And in the wake of the administration of President George W. Bush, whose vice president, Dick Cheney, became the most powerful vice president ever to hold the office, discussion of the vice president's role is a hotter topic than ever before.

In this article, we'll examine the misunderstood office of the vice president and look at some of the people who've made it what it is today.

Advertisement