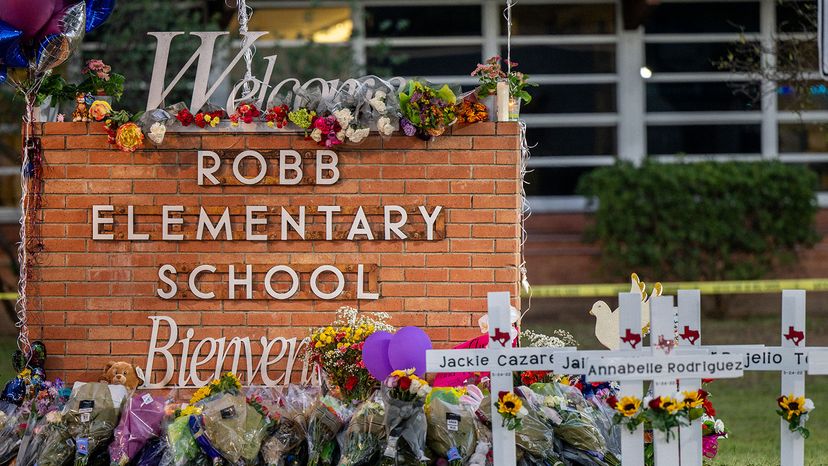

On the morning of May 24, 2022, in Uvalde, Texas, an 18-year-old gunman named Salvador Ramos shot his grandmother in the face, and then sent a text message to a 15-year-old girl in Germany whom he'd met on the internet. "Ima go shoot up a elementary school rn," he reportedly wrote. Then Ramos took his grandmother's truck and drove to nearby Robb Elementary School. After crashing the truck into a railing nearby, he continued on foot to the school and walked inside, carrying a semi-automatic military-style rifle that he'd recently purchased, and began shooting. By the time the slaughter had stopped, 19 children and two teachers were dead. So was the teenage gunman, who had been shot to death by a tactical team [sources: Hernandez et al.; Bogel-Burroughs; Levinson et al.].

For a nation that has seen a string of mass shootings over the past two decades, it was yet another collective trauma. What was even more shocking to some was the ease with which Ramos, a teenager whose behavior reportedly had grown increasingly troubling and violent, had been able to legally obtain weapons The day after Ramos turned 18, he went into a local store and purchased a semi-automatic rifle, and in the several days that followed, he purchased 1,657 rounds of ammunition and a second semi-automatic rifle [sources: Klemko, Foster-Frau and Boburg; O'Kane].

Advertisement

And once again, as they have so many times in the past, gun control advocates called for stricter laws to prevent such tragedies. "We have to act," President Joe Biden, a longtime advocate of gun control, said in a TV address on the evening after the Uvalde mass shooting [source: Whitehouse.gov].

Tragic events spark fear and outrage, drive up gun sales and, conversely, inspire calls for expanded (or better-enforced) gun control. This has been the pattern for the past half-century, since Congress passed the Gun Control Act of 1968 following the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The Brady Act, which requires background checks by licensed dealers (but does not apply to gun shows), arose from the 1981 assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan [sources: ATF; Hennessey and Mascaro]. The act is named for James Brady, Reagan's press secretary who also was injured in the attempt and went on to become a gun control advocate.

The possibility of legal reform remains unclear, and the composition and effectiveness of such laws remains hotly debated.

One proposed gun law reform involves banning assault weapons such as the popular AR-15, the semi-automatic rifle used in numerous mass shootings, including the 2012 attack on Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, which took the lives of 20 young children and six teachers, and the slaughter of 59 people by a gunman who fired on a concert from a hotel room window in Las Vegas in October 2017 [source: Blankstein et al., Calabrese and Siemaszko]. Such a ban was passed by Congress in 1994 and stayed in place for a decade, before it was allowed to lapse in 2004. Attempts to revive the measure have failed, though some Republicans are now saying they are open to banning AR-15s in light of the Uvalde school shootings.

After the 1994 law was passed, public support for gun control receded. In 1991, a Gallup poll found that 78 percent of Americans favored stricter regulation of the sale of guns, but by 2011, the year before Sandy Hook, just 44 percent of Americans supported tougher laws. Since then, support for tougher regulation has risen and fallen, perhaps driven by repeated instances of mass killings, and settled at 52 percent in 2021 [source: Gallup].

Other pollsters have seen similar fluctuation. A poll conducted by Quinnipiac University in the wake of the Parkland mass school shooting found strong support for various gun control measures. Sixty-seven percent of Americans favored revival of the assault weapons ban, and 97 percent favored universal background checks on gun purchasers. (Currently, people can avoid such screening if they buy from private owners or at gun shows.) An April 2021 Q poll, however, found that support for an assault weapons ban had declined to 52 percent, and support for universal background checks had dropped to 89 percent [sources: Quinnipiac, Cook, Quinnipiac].

In the U.S., the gun control debate comprises strongly held views about constitutional law, the rights of the individual, the role of the state and the best way to keep society safe. But it also encompasses an important practical question: Do countries with stricter gun laws experience less crime or fewer homicides?

The answer is anything but simple.

Advertisement