Controversy: Rehabilitation or Punishment?

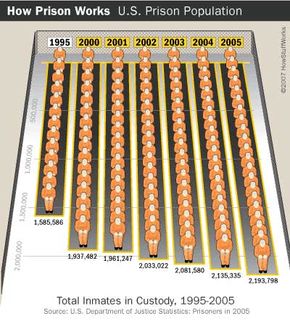

As of December 31, 2005, 2,193,798 people were in federal, state or local jails and prisons. That equates to 491 prisoners per 100,000 U.S. citizens. In addition, imprisonment rates have been increasing steadily since the 1980s, and most prisons are overcrowded. A 2005 Department of Justice report shows that the federal prison system and those of 23 states are operating at or above maximum capacity. Prison populations do not reflect the gender and racial make-up of the rest of society: 39.5 percent of inmates in 2005 were black, 20.2 percent Hispanic. Less than 10 percent of all prisoners are female.

Prison conditions and the treatment of inmates are regulated at several levels. The highest level is the U.S. Constitution. The Eighth Amendment reads: "Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted." Legal precedent is used to determine what constitutes cruel and unusual punishment, since the amendment's wording is vague. International law also regulates prisoner treatment through the treaties known as the Geneva Conventions.

Advertisement

Essentially, these treaties require that prisoners be clean, safe, and properly fed with access to adequate medical care. Records should be kept of their presence and status within the prison, and all their basic human rights should be recognized to the extent possible within a prison. Torture is forbidden, along with other forms of brutality. Some people (some of them prisoners) claim that maximum and medium security U.S. prisons in the 21st century continue to violate many of these rules.

When most people hear about unpleasant conditions in prisons, they don't feel particularly bad for the convicts. However, there has been a prison reform movement since at least the 1700s, when religious groups such as the Quakers objected to prison conditions. Reformers lobby for better treatment by guards, better equipped medical facilities, well-funded education programs and more humane treatment. These people aren't criminal sympathizers -- they simply have strong beliefs, for ethical or religious reasons, that even convicted criminals should be granted basic human rights.

There's another reason people want to reform prisons. More than 90 percent of all prisoners are eventually released [Source: U.S. Department of Justice]. When they are released, often the only skills they acquired in prison were those that allowed them to survive. They may be paranoid or bitter. They may have learned that the only proper response to a problem is violence. Their social skills have atrophied. Getting a decent job as a convicted criminal is hard enough -- add in these factors and it can become very difficult for ex-cons to reassimiliate themselves into the outside world.

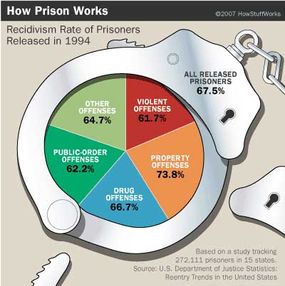

A study of state prisoners from 15 states who were released in 1994 showed that more than half of them ended up back in prison within three years [Source: U.S. Department of Justice]. Sixty-seven and a half percent of them were arrested for a new crime, unrelated to their prior charges. The goal of many prisoner reformers is to reduce these rates by providing education and job training for inmates. All prisons offer a GED course (it is often a requirement for parole) and a few vocational courses. In many states, there are plenty of programs "on the books" that inmates can use to better themselves, but not everyone is willing to devote budget money to people who can't vote (only four states allow inmates to vote, while 11 states ban convicts from ever voting again for the rest of their lives).

On the day a prisoner finally completes his sentence, he is given little. He may get the clothes and items he had with him when he arrived at the prison, although some things may be missing. He will get whatever money is in his prison account, though it doesn't usually amount to much. If the prisoner has no street clothes, he is given a prison uniform to wear. If he has no money, he'll get $5 so he can afford bus fare home, if he has a home to return to after his time in prison.

Related Articles

More Great Links

Sources

- Alton Historical Society. "Alton in the Civil War: Alton Prison." http://www.altonweb.com/history/civilwar/confed/

- Center for Policy Alternatives. "Privatizing Prisons." http://www.stateaction.org/issues/issue.cfm/issue/PrivatizingPrisons.xml

- Clinto, Susan. Correction Officer (Careers Without College). Capstone Press, March 1998. ISBN 0516212796.

- Harrison, Paige M. and Beck, Allen J., Ph.D. "Prisoners in 2005." Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin, November 2006. http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/p05.pdf

- Hjelmeland, Andy. Prisons: Inside the Big House. Lerner Publications, June 1996. ISBN 0822526077.

- Human Rights Watch. Prison Conditions in the United States: A Human Rights Watch Report. ISBN 1564320464.

- Kolodner, Meredith. "Immigration Enforcement Benefits Prison Firms." New York Times, Jumy 19, 2006. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/19/business/19detain.html? ex=1310961600&en=6389a8c6c55d466a&ei=5088&partner= rssnyt&emc=rss

- Langan, Patrick A., Ph.D. and Levin, David J., Ph.D. "Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 1994." Bureau of Justice Special Report. http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/rpr94.pdf

- Lerner, Jimmy A. You Got Nothing Coming: Notes From a Prison Fish. Broadway, October 14, 2003. ISBN 0767909194.

- Martin, Mark. "Prison budget up, despite no raise." San Francisco Chronicle, May 14, 2004. http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/ 2004/05/14/MNGE46LJUA1.DTL

- Ross, Jeffrey Ian and Richards, Stephen C. Behind Bars: Surviving Prison. Alpha, May 1, 2002. 0028643518.

- Smith, Jeffrey R. "2006 Budget Proposal: Agency Breakdown." Washington Post, Feb. 7, 2005. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/interactives/budget06/ budget06Agencies.html

- Sullivan, Larry E. The Prison Reform Movement: Forlorn Hope. Twayne Pub, May 1990. 0805797394.

- Tayoun, Jimmy. "Going To Prison?" Biddle Pub Co, January 2002. 1879418339.

- U.S. Bureau of Justice. "Prison Statistics." http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/prisons.htm

- U.S. Bureau of Justice. "Reentry Trends in the United States." http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/reentry/reentry.htm