Do you remember voting for the president in a mock election in elementary school or junior high? Maybe you selected your candidate at random because you didn't really know the difference between the two (or care). Well, now you're older and wiser and know that who you vote for does make a difference. Or does it?

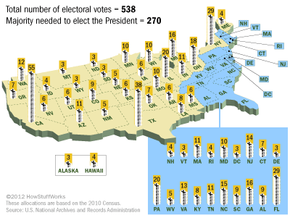

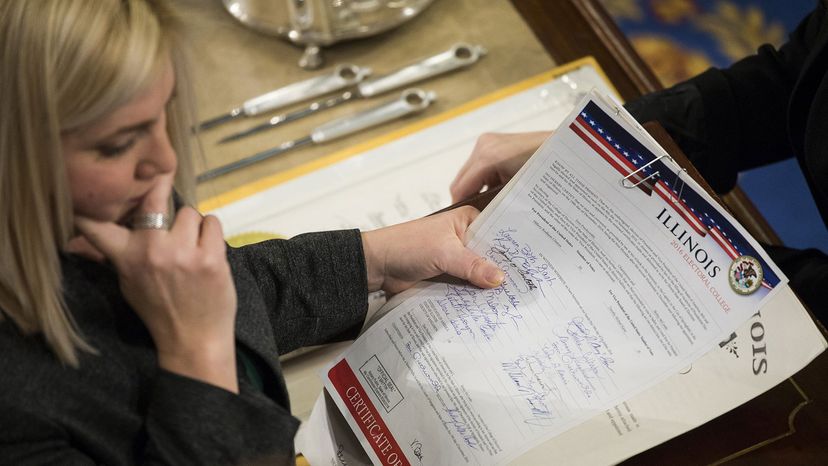

Take the Electoral College, for instance. Every four years, on the Tuesday after the first Monday of November, millions of U.S. citizens go to local voting booths to cast a vote for the next president and vice president of their country. Their votes are recorded and counted, and the winner is declared — unless the majority of Electoral College members vote for another candidate, of course [source: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration].

Advertisement

Truth is, the results of the popular vote are not guaranteed to stand because the presidential election is really decided by the votes of the Electoral College. Although this could feel as though your vote is about as decisive as those of an elementary school election, the Electoral College process was actually put in place to ensure a nationwide system of fairness. When you cast your vote for president, you also vote for an often-unnamed elector who will cast a ballot in a separate election that ultimately will choose the president.

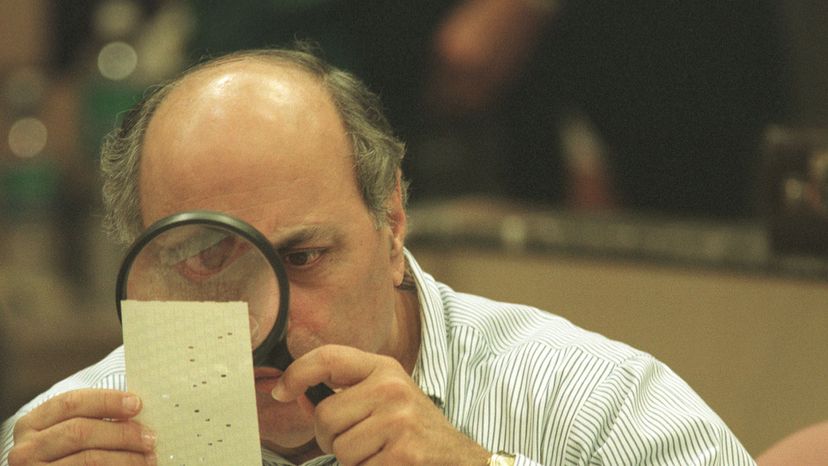

For some of us, the Electoral College process (and its outcome) may seem a bit shocking. In the 2000 U.S. presidential election, for example, more Americans voted for Gore, but Bush actually won the presidency because he was awarded the majority of Electoral College votes. It's a political upset that's occurred several times since the first U.S. presidential election; five presidents have been elected by the Electoral College after losing the popular vote.

By now you're probably wondering how — and why — the Electoral College began. We'll explore its historic start in the next section.