For more than 80 years, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has worked to defend fundamental rights such as freedom of speech, freedom of religion and the right to privacy. The efforts of ACLU attorneys have also influenced interpretations of U.S. Constitutional law. The ACLU has grown to include more than 400,000 members and handles around 6,000 court cases each year [ref].

However, the ACLU and controversy are never far apart. It has most often come under attack from conservatives and the government, but its defense of religious figures and neo-Nazis has drawn the ire of liberals as well. In this article, we'll find out what the ACLU does and where it came from. We'll also learn why it's so controversial.

Advertisement

The ACLU is a non-profit organization that provides legal aid to people whose cases fall under its mission. According to the ACLU's Web site:

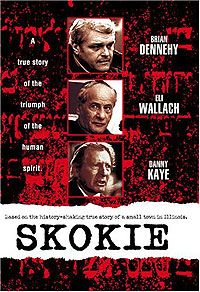

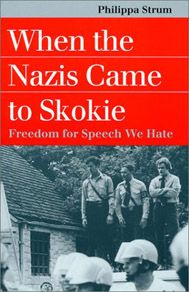

The defense of liberty seems innocuous. So why is the ACLU so controversial? Simply put, the organization holds an absolutist view of liberties -- they defend all people whose liberties have been violated, even if their views, ideas or actions are unpopular. Therefore, the ACLU ends up defending Nazis, pornographers, religious zealots and extremists of all types.

The point of such unpopular cases is to protect the rights of all minorities. Many minorities do have unpopular points of view. In the ACLU's eyes, the right of a Nazi group to freedom assembly is just as important as, for example, Native Americans' freedom of assembly. Allowing the government to restrict any group's freedoms would invite restrictions on other groups.

Of course, this philosophy draws a lot of opposition, on both the left and the right. The United States already draws a line between speech protected by the First Amendment and unprotected speech: child pornography, for example, is unprotected. Some feel that hate speech should be similarly restricted, while others argue that anti-war or anti-government speech during a time of war or national crisis should be restricted (as it has been at many times throughout U.S. history).

Advertisement