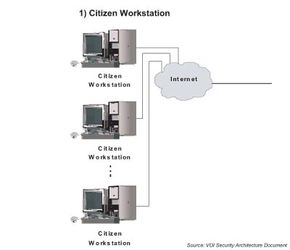

Imagine logging into a computer terminal – perhaps your own personal computer -- and, with a couple of quick clicks, exercising your Constitutional right to cast your vote in a federal election. Will sidestepping the nuisances of finding the correct polling location and standing in line for hours increase voter participation? How close are we to seeing such a system in place?

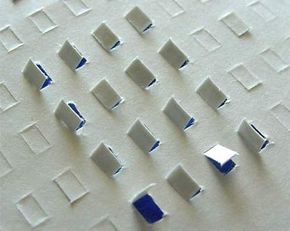

Voting via the Internet is just one form of electronic voting (e-voting). Generally speaking, e-voting refers to both the electronic means of casting a vote and the electronic means of tabulating votes. Using this definition, many voting methods currently in use in the United States already qualify. Punch cards and optical scan cards are tabulated using electronic means, for example, and they have been in use for decades.

Advertisement

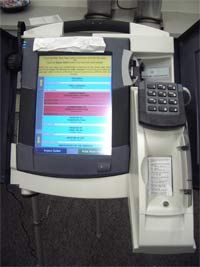

Recent applications that fall under this definition include Direct Recording Electronic (DRE) systems and voting via the Internet. Most people think of DRE systems when talking about electronic voting, as these electronic systems are the first with which the general public has interacted. Not coincidentally, these new systems are also the subject of a lot of criticism and scrutiny.

In this article, we will examine how elections are administered, the various methods of electronic voting and advantages and concerns related to each method. We’ll also examine how electronic systems may be used in future elections.

To understand the role voting systems play in the election process of the United States, we need a quick primer on election administration. Individual states oversee elections -- even the federal ones. The reason for this decentralized approach is mainly due to scale. According to Election Data Services, there are over 170,000,000 registered voters in the United States. Imagine coordinating, facilitating and tabulating votes for that many people. A centralized voting system is not a realistic choice once you see the size of the task.

For a presidential election, you would go to your local polling facility during polling hours. There a local election official or volunteer would verify that you are a registered voter and you would vote. Once the polls close, an election official would gather the ballots and transport them to a centralized tabulation site. Here, officials would count the votes and then report the results. Electors from your state would later cast their vote for one of the presidential candidates. Usually an elector will vote for whichever candidate received the most votes in the elector's state. However, they are not obligated to vote along the same lines as the popular vote. Check out How the Electoral College Works to learn more.

In 2002, Congress passed the Help America Vote Act (HAVA). This legislation has three primary goals:

- Create a federal agency to serve as a centralized point for election administration information

- Provide funding to states to improve election administration and update voting systems

- Create minimum standards for states to follow in election administration

States received a total of $3.9 billion dollars, with the amount paid to each state determined by the size of its voting-age population. Many states used the funding to upgrade old voting systems.

In the next section, we will look at the two types of electronic voting systems: paper-based and direct-recording.

Advertisement