Across the U.S., an increasing number of people want a better way to elect leaders in what has become a hyper-partisan political system they see as deeply dysfunctional. Voters argue that the problem with the traditional winner-take-all system (also known as plurality voting) is that only the two major-party candidates have a realistic chance of winning, and third-party candidates are relegated to being spoilers. Major-party candidates can focus on their base, ignore the views and concerns of people in the middle, and still win, sometimes with less than majority support.

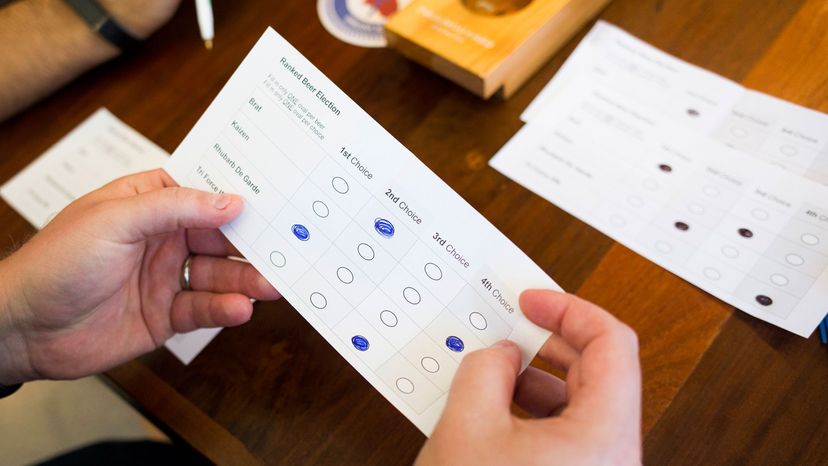

Now New York City voters will get the chance to put ranked-choice voting to the test in its mayoral primary race — the most high-profile test of the voting system gaining ground across the U.S. (San Francisco and Minneapolis, have been using it for years to elect local officials [source: FairVote]. In ranked-choice voting, instead of picking a single candidate, voters rank several candidates in order of preference — and then have their preferences reallocated in runoffs, if necessary, until there's a winner with majority support.

Advertisement

"I think we essentially have a deep problem with plurality voting — it doesn't fit a multiple-options society," Rob Richie, executive director of the electoral reform group FairVote, told the Atlantic in 2016.

Proponents say ranked-choice voting would free Americans from the fear that they are "wasting" their votes on third-party candidates, and give major-party politicians a powerful incentive to reach out to more voters and listen to their concerns. Critics, in contrast, fear the system would confuse voters and instead of raising turnout, depress it even more.

In this article, we'll look at how ranked-choice voting works, and whether it really would improve American politics.

Advertisement