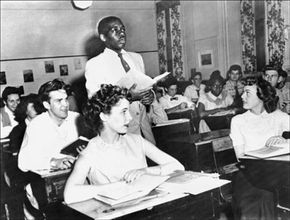

In 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court heard 78 cases on issues including terrorism, water rights, firearms and immigration [source: On the Docket]. As the highest court in the land, it serves as the ultimate decider in cases that can alter the law and influence society for generations to come. Take, for instance, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the 1954 ruling that struck down the concept of "separate but equal" and declared racially segregated public schools unconstitutional. That decision helped spark the Civil Rights Movement, which changed the course of American history.

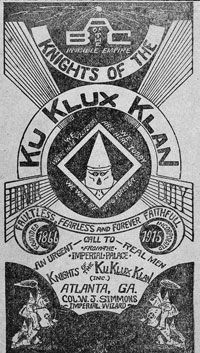

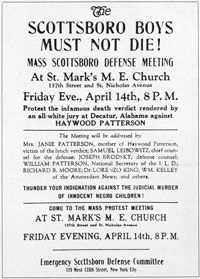

But landmark court decisions such as Brown v. Board are rarely met without debate. People on both sides of the aisle may disagree with a judge or jury's ruling, sometimes boiling over in violence. Although the fundamentals of the American judicial system are centered on the concepts of innocent until proven guilty, trial by jury and due process, the public may not always believe that those tenets were upheld during trials.

Advertisement

Are there times when the courts fail to truly resolve a problem? What happens when these legal structures create more questions than they answer? To answer that, let's take a look at some of the most controversial cases in the history of the United States. Each produced some sort of verdict, but the outcomes left many doubtful about whether justice was truly met.