Key Takeaways

- Shabbat is the Jewish Sabbath, a 25-hour day of rest that begins Friday evening and ends Saturday night.

- Shabbat is a holy day blessed by God, observed through lighting candles, sharing meals, and spending time with family and friends.

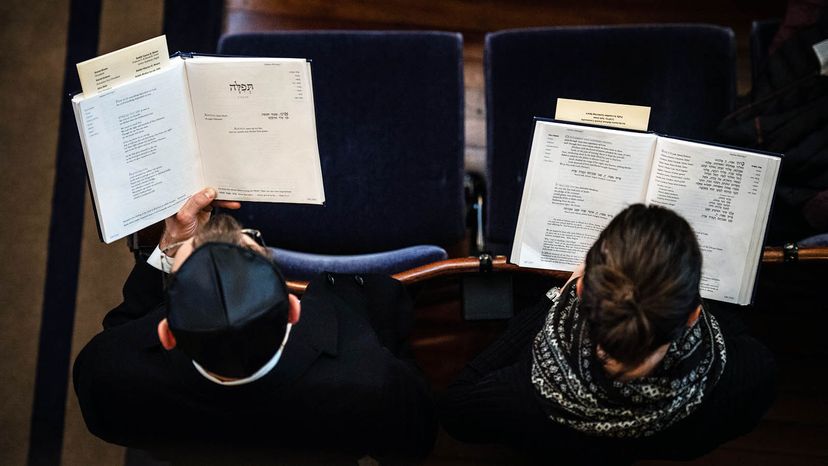

- Shabbat observance includes following specific rules and traditions, such as refraining from certain activities and attending synagogue services.

Shabbat is the Jewish Sabbath, a 25-hour "day of rest" that begins at sundown Friday evening and ends Saturday night when, according to Jewish tradition, it's dark enough to see three stars in the sky.

During Shabbat, Jewish people take time out from the busy workweek to light candles, eat a delicious meal with family and friends, perhaps attend services at the synagogue or just go for a long, leisurely walk. Shabbat is more than a "day off;" according to the Torah (the first five books of the Hebrew Bible) it's a holy day blessed by God.

Advertisement

"In Judaism, when you wish somebody a happy Sabbath, you say 'Shabbat shalom,' which means 'Sabbath peace,'" says Rabbi Ron Isaacs, author of "Shabbat/dp/0765760193">Every Person's Guide to Shabbat."

"In our busy lives, it's very difficult to have even one minute of peace and tranquility, but Shabbat often did it for me," says Rabbi Isaacs, reflecting on when his children were young. "When I was sitting with my family watching two candles burn, singing songs around the dinner table, having a time when I didn't have to rush, not looking at my phone, that was very peaceful."

Advertisement