Untraceable: History of the Roma

Though they spread across Europe relatively quickly, reaching as far West as England by 1514, it took centuries to piece together the Romani past [source: McDowell]. The Roma never kept genealogical records, allowing a nefarious mythology about the mysterious wanderers with their colorful caravans to substitute for fact. As a result, by the time a Hungarian theologian studying in Holland took an interest in unraveling the roots of the Romani language in 1760, the gypsies had become a people with a collective history that's nearly untraceable [source: Hancock].

Romani vocabulary, dappled with Sanskrit, led a series of scholars back to northern India, and genetic testing has further confirmed that the Roma emerged not in Romania, and certainly not in Egypt, but in India [source: Brownlee]. Scholars have debated the date and cause for the gypsies' exit out of India, with some postulating a migration as early as 700 AD, though many agree that it happened a few centuries later [source: Fonseca].

Advertisement

During the 11th century, Mohammad of Ghazni wanted to spread Islam to northern India by force, raiding the region from 1000 to 1027 AD [source: Hancock]. To ward off the Muslim warriors, the local Hindus organized an army referred to as Rajputs, which was defeated by the Ghaznavids and taken captive. Then along came the Persian Seljuks who conquered the Ghaznavids and took the Rajputs out of northern India into modern Turkey as their empire expanded [source: Hancock]. By 1300, the Rajputs had coalesced into a multi-ethnic group and crossed from Asia into the Balkans, which remains their adopted homeland. These displaced warriors are widely thought to be the gypsies' predecessors.

The gypsies themselves, however, only believe one fact about their history with absolute certainty: They came from India [source: Roma Foundation]. Lacking a homeland and a documented history makes it difficult to connect the dots among all of the tribes, and writers who have spent time with Roma around the world often mention the people's general disinterest in the past. For gypsy tribes, their ethnic history merely extends across the memory span of their oldest member [source: Fonseca].

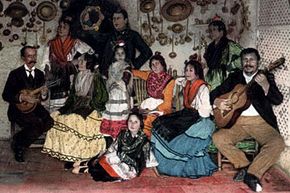

As the Roma moved into Western Europe, they weren't received with open arms. Beginning in the early 15th century, thousands of Roma were forced into slavery for more than 400 years in regions of modern-day Romania [source: Fonseca]. Elsewhere, the darker Romani complexion, mottled dialects and non-Christianity attracted xenophobic discrimination, which persists even today, despite the fact that many present-day gypsies are Christian. Refused service in stores, the Roma sometimes resorted to thievery, and refused employment, they often relied on entertainment-related jobs, such as music and fortune telling, to make ends meet [source: Hancock]. The Roma likewise met the gadje, or non-Roma, with suspicion as well, resisting cultural assimilation and remaining on the shunned outskirts of mainstream society.

The most egregious example of Roma persecution occurred during World War II. In 1937, the Nazis amended the Nuremburg Laws to include "gypsies" as classified second-class citizens and ordered them sent to concentration camps [source: Fordham]. While the Jews suffered the greatest number of casualties during the Holocaust, the Nazis also gassed Roma families by the thousands. By the end of the War, an estimated 500,000 European Romani had been executed, and gypsies refer to the extermination as porraimos, or "the great devouring" [source: Godwin]. Yet as a horrifying testament to the cross-cultural revulsion directed toward the gypsies, their Holocaust experience was never addressed during the Nuremburg trials. Since World War II, only one Nazi was ever officially punished for crimes against gypsies [source: Fonseca].