It's safe to say that just about every American has at least heard of the American dream. For years, politicians have lauded it in speeches, or warned it would be in grave danger, if their political opponent was elected. Popular songwriters, from Neil Diamond to Tanya Tucker, have celebrated the pursuit of it. Hundreds of books include the words "American Dream" in their titles; some are guidebooks on how to reach it, like Suze Orman's 2011 tome "The Money Class: Learn to Achieve Your New American Dream." There may be no greater compliment to pay an American citizen than to say he or she has lived out the American dream.

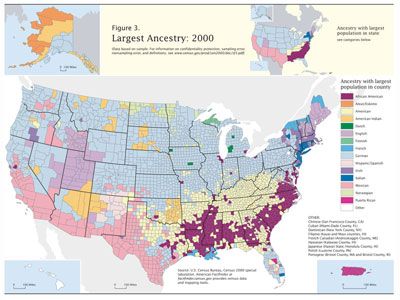

Considering the fact that Americans are so enamored with the American dream, it's all the more strange that no one has been able to agree what it means. To some, it's the faith that anyone who lives in this country -- even a penniless immigrant, slum dweller or child of a hardscrabble farmer -- has the potential to prosper and become wealthy. To others, it's the belief that everyone in America has the opportunity to pursue his or her great passion. To others, such as folksinger/activist Woody Guthrie -- whose most famous composition, "This Land is Your Land," is sung today by schoolchildren across the nation -- and civil rights leader Martin Luther King, the American Dream means that every citizen of the land is guaranteed equality, freedom and the right to be heard.

Advertisement

But not everybody thinks the American dream is a positive thing. Some say it's degenerated into a compulsion to amass possessions and property, and is leading the nation to ruin. For example, Harvard University business professor John A. Quelch writes that our political leaders are guilty of "defining the American Dream in material terms, in encouraging Americans to live beyond their means in its pursuit, and then putting in place policies that enable them to do so" [source: Quelch]. Other opponents, noting that ethnic and economic inequality persists in America, dismiss the American dream as nothing more than a cruel myth. Comedian, author and social critic George Carlin once famously wisecracked: "It's called the American dream because you have be asleep to believe it" [source: Carlin].

Whatever you think of the dream, you're probably wondering where it came from. Find out about the origins of the American dream on the next page.