Alexander Hamilton, one of the framers of the U.S. Constitution, was far from comfortable at the thought of instituting a democracy. Democracy was, in Hamilton's opinion and those of many others at the time, tantamount to mob rule. The idea of a large, diverse group of people attempting to govern itself invoked images of gangs tarring and feathering the local tax collector. That's not government, went the argument: That's lawlessness.

What Hamilton endorsed instead was a strong, centralized government run for the benefit of the whole by an elite ruling class [source: Wright and MacGregor]. That seems miles away from American democracy, though it's pretty much how the United States operates. The U.S. system of government is a republic, a type of democracy in which elected officials carry out the will of the people. These officials, called politicians, should know more about issues that face the society and how the government functions than the average citizen does. This means they're entrusted to speak on behalf of the people they represent. The citizens bestow their trust by voting officials into office.

Advertisement

A true democracy is slightly different. In a democracy, the will of the people serves as the basis for collective decisions. It's also called self-governance. Each member of the population expresses his or her opinion on each issue through voting. Since all votes are equal, the opinion held by the most members is considered the will of the majority. That's what becomes law.

In this sense, the U.S., which serves as the model for democracies around the world, can't use its 250 years of existence as proof that democracy works in practice. Also keeping the U.S. from serving as a true democratic model is the argument that it hasn't been even a republican democracy for more than a couple of decades.

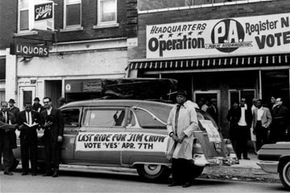

One of the tenets of a democracy is that all members of the society must be equal. For the democracy to function, this equality must be present in the individual vote. Author N.D. Jayaprakash points out that in the U.S., groups have been disenfranchised from the right to vote. Initially, only white men wealthy enough to own land could vote, then all white men, then African-American men. It wasn't until 1920 that women gained the right to vote, and because of post-Reconstruction Jim Crow laws, blacks were effectively barred from voting until the 1960s. Jayaprakash argues that it wasn't until the mid-1990s, when the National Voter Registration Act came into effect, that most Americans enjoyed wide access to exercise their right to vote [source: Jayaprakash].

All of this is to say that the democratic experiments represented by nations like the U.S. and others don't necessarily serve as true examples of democracies. Those that do are still too young to act as any real proof of whether a true democracy works. But what about theoretically?

Advertisement