When President William McKinley walked into the Palace of Music at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, on Sept. 6, 1901, he was an enormously popular figure with an accomplished record as chief executive. That's why, despite the intense heat, so many people had lined up to meet him at the scheduled reception. But when he stretched out his hand to a 28-year-old former steelworker named Leon Czolgosz, the young man pulled a .32-caliber pistol from his pocket and fired two bullets at point blank range.

President McKinley died of his wounds eight days later, and Czolgosz was executed the next month. The assassin was an avowed anarchist, and his reason for killing McKinley had nothing to do with the president personally; rather, he was motivated by an ideological belief that powerful rulers should be eliminated. There is no small irony in this because Czolgosz's action handed the presidency to a man who would do more to expand executive power than any president before him [source: Andrews].

Advertisement

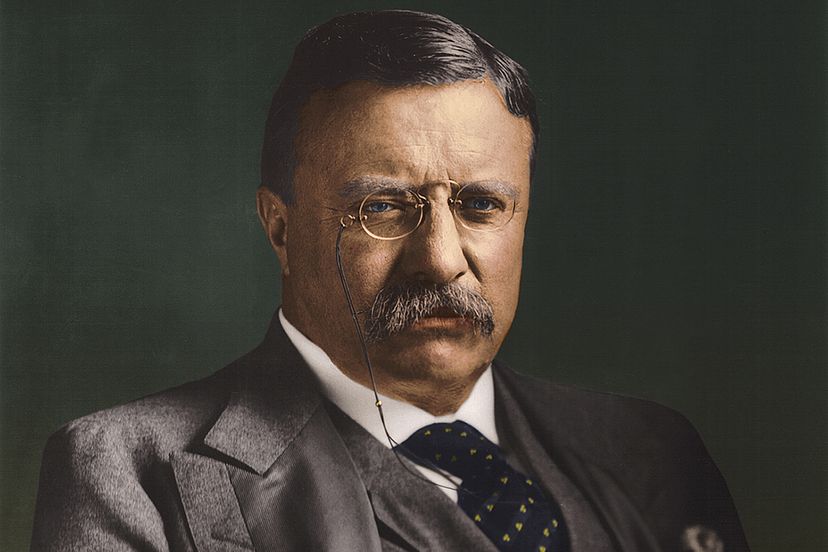

Theodore Roosevelt had made his name as the commander of the Rough Riders cavalry unit in the Battle of San Juan Hill in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. After the war he successfully campaigned for the governorship of New York where he established a record as a popular and effective reformer. But this was the era of "political bosses," when powerful, unelected men smoking cigars in back rooms could make or break a political career. The political boss of the Republican Party in New York at the time, a man named Tom Platt, didn't want a reformer and decided to prevent a second Roosevelt term by shuffling the brash young politician into the innocuous role of vice president. As with the actions of the anarchist assassin, this strategy would backfire.

Theodore Roosevelt would be a ruler and reformer unlike any the country had ever seen. At 42, he was, and still is, the youngest person to have ever held the office of U.S. president. His view of his new position was simple, but unprecedented. Whereas previous presidents had, for the most part, followed the general rule that their role was to execute the laws created by Congress, Theodore Roosevelt felt that as Commander in Chief he was free to do as he pleased wherever, and whenever, he pleased unless the law specifically said he couldn't [source: Theodore Roosevelt Association]. It was a political philosophy that would change the U.S. presidency forever, ushering in a new era of executive power.

Advertisement