Singer, actor and television host RuPaul has been touted as the most famous drag queen in the world and has helped bring the campy performance-oriented brand of cross-dressing into mainstream popular culture. In 1994, RuPaul's sassy single "Supermodel (You Better Work)" broke into the top 30 on Billboard Music's pop chart, catapulting the multitalented personality into a successful career with résumé highlights including a high-profile cosmetics campaign, bestselling autobiography and hit reality television series. But RuPaul isn't the first man to become a household name by donning a dress and high heels.

During the early 20th century, Julian Eltinge, born William Dalton, became internationally famous for his uncanny ability to act like a lady. Details surrounding his initial interest in mimicking women's fashion and body language are hazy, as origin stories offer different theories, such as Eltinge's mother dressing him up like a girl, him stumbling on his gender-bending knack while taking dance lessons and female impersonation on stage being a lifelong dream of his [sources: Landis, The Julian Eltinge Project]. Whatever the preceding events, in 1911 Eltinge won theatrical acclaim for his cross-dressing role in the hit play "The Fascinating Widow," which would open the door to his ultimate status as the father of modern drag queens. Transitioning from the stage to the silent silver screen, Eltinge commanded one of the highest salaries in show business at the time, launched three fan magazines dedicated to his craft, accumulated a cabinet's-worth of product endorsements and even performed for a delighted King Edward VII of the United Kingdom.

Advertisement

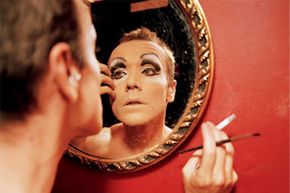

Considering the era's restrictive views on gender and widespread disavowal of homosexuality, Eltinge's onstage drag performances surprisingly didn't ruffle many contemporary feathers; female audiences in particular delighted in Eltinge's seemingly magical transformations into women. But in his personal life, Eltinge displayed a distinct unease with his stage trickery of posing as female characters. Extremely concerned that fans might assume he cross-dressed offstage or, even worse at the time, engaged in sexual relationships with men, the bachelor made well-publicized displays of his masculine passions and pastimes that included boxing, cigar smoking and fishing.

By the 1930s, Eltinge's silent film star had faded as "talkies" attracted larger audiences at the cinema, and his gender metamorphosis shtick had lost its novelty. His story, however, is only one pit stop along the extensive historical highway of cross-dressing and drag queens.

Advertisement