As the holidays close in, parents inevitably remind unruly children that Santa Claus is watching them. But there's another lurker out there in the long dark night, and he's watching too — a thing of fur and horns and cloven hoof.

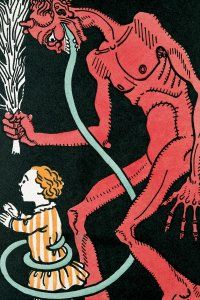

Yes, Virginia, there is a Krampus, and for naughty kids, this demonic beast-man brings chains and switches instead of toys. Every Dec. 5 — the Krampusnacht Eve of the Feast of St. Nicholas — he descends from the mountain wilds to terrorize children and drag the worst of their lot away in a foul wicker basket.

Advertisement

While he's not the only yuletide bogeyman in Western tradition, Krampus has clawed his way to the front of that frightening pack. Unlike Iceland's Grýla the Ogress or France's Père Fouettard, Krampus has not only survived within his native Germanic Alpine traditions, but he's also managed to achieve international notoriety.

Before we explore the history, psychology or even anatomy of Krampus, you're probably wondering why yuletide bogeymen even exist. Surely, the holidays are a time of light and childlike wonder — not monstrous kidnappers!

Ah, but the holidays, at least in northern latitudes, have always been a time of darkness. Sure, we light trees, sing carols and feast upon the spoils of hunt and harvest, but the wintertime future is uncertain. Will spring thaw our frozen world? Will our crops grow again? Will our larder be enough to make it through the winter?

That's one reason why, if you venture through world mythology, you'll pass countless devils, satyrs and horned spirits who all resemble old Krampus. In Greek mythology, for instance, you'll find Hades' abduction of Persephone, the daughter of harvest goddess Demeter. It's a tense piece of drama that explains the Earth's seasons: winter arrives when Persephone must enter captivity in Hades, spring returns when she emerges again each year. The tale serves as an iconic reminder that winter is an inherently apocalyptic time, pitting the forces of order and life against darkness and death.

These very motifs permeate many early religions, and when Christianity spread through Europe, these old gods and spirits never quite died out. Rather, people wove them into the new religious tapestry. In fact, early Christians transplanted the birth of their savior Jesus Christ to Dec. 25, as this was a date associated with older celebrations of the new sun — that resurgent celestial force destined to defeat the long winter.

And so Krampus ties into a rich legacy of winter darkness, seasonal fear and pre-Christian traditions involving harvest spirits and wild men. On the next page, we'll get to know the old chap.

Advertisement