Key Takeaways

- The Beatitudes are a list of blessings given by Jesus in the New Testament, challenging societal norms by blessing the poor, meek and persecuted.

- There are two versions of the Beatitudes in the Bible, with Matthew's version being longer and more well-known than Luke's.

- The Beatitudes can be interpreted as commandments to follow, descriptions of those who are blessed or invitations to live as Jesus did.

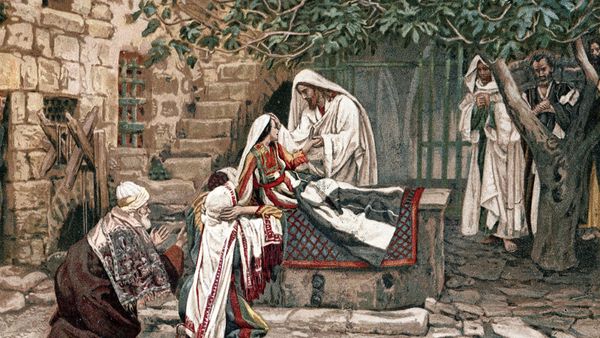

In the New Testament, the Beatitudes is the name for the opening verses of the "Sermon on the Mount," considered to be the heart of Jesus' teachings. Jesus began each Beatitude with the words "Blessed are ..." which in Latin is written beati sunt. That's why we call them the Beatitudes, because they're a list of beati.

For nearly 2,000 years, theologians, scholars and everyday Christians have wrestled with these "paradoxical" blessings, says Rebekah Eklund, a theology professor at Loyola University of Maryland and author of "The Beatitudes Through the Ages."

Advertisement

The Beatitudes are paradoxical, and even "countercultural," says Eklund, because they go against the standard "wins" of secular culture. Jesus blesses the poor and hungry, not the rich and comfortable. He blesses the meek and mistreated, not the strong and popular.

But if the Beatitudes are commandments, as many Christians have interpreted them, then how are we supposed to follow them? Does God really want us to be poor and hungry? Is it a sin to be rich? Or do the Beatitudes serve a different function? Let's start by taking a closer look at the two different versions of the Beatitudes and where they came from.

Advertisement