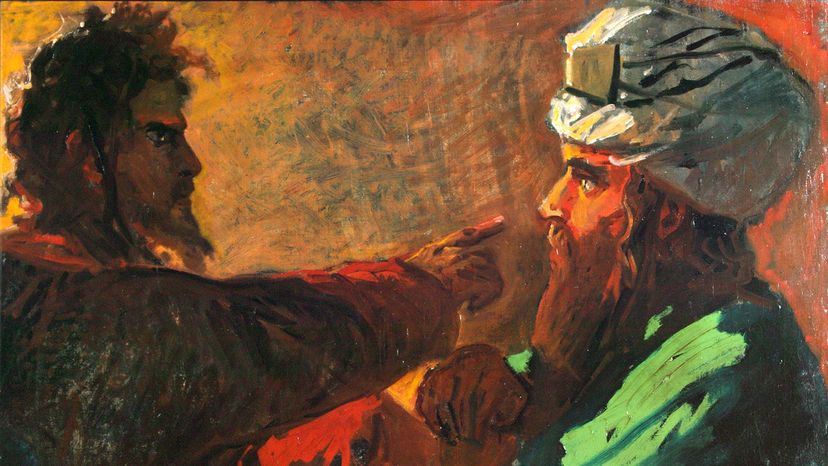

Jesus only loses his cool a handful of times in the New Testament (just ask the moneychangers in the Temple), but he unleashes one of his fiercest tirades in Matthew 23 against the Pharisees and other "teachers of the law."

Advertisement

Jesus only loses his cool a handful of times in the New Testament (just ask the moneychangers in the Temple), but he unleashes one of his fiercest tirades in Matthew 23 against the Pharisees and other "teachers of the law."

Advertisement

In verses 13-39, known as "the seven woes," Jesus calls the Pharisees "hypocrites" six times. He also calls them "blind" (five times), "children of hell," "a brood of vipers" and compares the false piety and posturing of the Pharisees to "whitewashed tombs, which look beautiful on the outside but on the inside are full of the bones of the dead and everything unclean."

The Pharisees of the New Testament are clearly cast as the bad guys, the perfect ideological and spiritual foils to Jesus and his followers. The Pharisees are portrayed as nitpicky enforcers of Jewish scriptures who are focused so intently on the letter of the law that they miss the spirit entirely. As Jesus says:

Advertisement

But does this picture of the Pharisees — as legalistic hypocrites — jibe with what historians and religious scholars know about the actual Pharisaic movement, which gained prominence during the Second Temple period of Judaism?

We spoke with Bruce Chilton, a religion professor at Bard College and co-editor of "In Quest of the Historical Pharisees," to better understand what the Pharisees really believed and why they clashed with the early Christians.

Advertisement

During the first century C.E., when Jesus lived, the Pharisees emerged as a religious movement within Judaism, not a separate sect. The Temple still stood in Jerusalem and it was the center of Jewish life. One of the greatest concerns of Temple rites was purity: that both the people who entered the Temple and the animals sacrificed there, were "pure" enough to satisfy God.

The Torah (the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, starting with Genesis) contains written commandments that explain the proper way to conduct Temple sacrifices, but the Pharisees believed they had additional divine instructions that had been passed down through centuries of oral tradition.

Advertisement

"The Pharisees believed that they had a special reserve of knowledge for determining purity," says Chilton. "They taught that their oral tradition went all the way back to Moses at Sinai, so not only was there a written Torah, which anyone could have access to, but there was also an oral Torah which was inside the Pharisaic movement."

What was distinctive about the oral law of the Pharisees was that it expanded the question of purity to life outside of the Temple. Even if a Jewish person lived far away from Jerusalem (in Galilee, for example) and wasn't planning to make a pilgrimage to the Temple, they could conduct their lives in such a way as to be pure enough to enter the Temple.

"In that sense, the Pharisees became a movement for the purity of the Jewish people," says Chilton.

The Pharisees were not, however, the powerful elite of first-century Judaism. Those were another Jewish sect: the Sadducees, the priestly class that controlled Temple worship and held the most political influence with the Roman Empire, which ruled over Palestine. The Sadducees rejected the oral law in favor of the written law established in the Torah.

The Pharisees were a working-class movement concerned with establishing a clear and consistent Jewish identity in everyday life. Interestingly, it was the Pharisees who believed in an afterlife and resurrection of the dead, both of which were rejected by the Sadducees as they were not mentioned in the Torah.

Another way Pharisees differed from Jewish tradition is believing that a messiah would come and bring peace to the world, though most of them did not think that messiah was Jesus.

Advertisement

The Pharisees are portrayed as a monolithic block in the New Testament, but Chilton says that while all Pharisees were concerned with purity, there was fierce debate among the Pharisees about how best to achieve it.

There were certainly Pharisees who believed that purity was obtained from the outside in, and who taught that ritual baths (mikvahs) and the ritual purification of cups and cooking implements was the only way to achieve purity. In Matthew 23, Jesus lambastes the pharisaic tradition of purifying the outside of cups and dishes while "inside they are full of greed and self-indulgence."

Advertisement

"Because Jesus himself was engaged in the issue of purity — but wasn't a Pharisee — his conflict with some Pharisees of his time was inevitable," says Chilton. "If you accuse somebody as impure, you're not saying purity doesn't matter; you're saying the opposite — there's a better way to achieve it."

But Chilton says there were other Pharisees who would have agreed with Jesus, that the true work of purification starts with a pure heart and faith in God. If you read the New Testament closely, in fact, you'll see that Jesus won sympathetic supporters and even followers from the ranks of the supposedly hated Pharisees.

Nicodemus, who visited Jesus at night to ask him questions, and then provided money and spices to give Jesus a proper Jewish burial after the crucifixion, was a Pharisee (see John 3). And in Luke 13:31, a Pharisee comes to warn Jesus that Herod wanted him killed.

But perhaps the most interesting and consequential mention of "friendly" Pharisees comes in the book of Acts, when a group of Pharisees is listed among the early followers of Jesus who remained faithful after his death.

As Chilton explains, though, those Pharisees took an ideological stance in opposition to influential apostles like Paul and Peter, which may explain why the Pharisees got such a bad rap in the New Testament.

Advertisement

In Acts 15, there is a meeting or "council" in Jerusalem attended by Paul, Peter, James, Barnabas and other apostles and followers of Jesus. The agenda of the meeting was to settle an important question among the early church: Did non-Jewish men need to be circumcised in order to be baptized and receive the Holy Spirit?

The Pharisees in attendance were the first to chime in. In Acts 15:5, it says:

Advertisement

Notice that it says the Pharisees were among the "believers," further proof some Pharisees, too, were early followers of Jesus.

But here's where things go south. The apostles are in stark disagreement with the Pharisees and say that everyone, circumcised or uncircumcised, can have their hearts purified through faith in Christ. Peter, acknowledging the physical pain and danger of circumcising an adult, rebukes the Pharisees in verses 10 and 11:

"By the time you get to this meeting in 46 C.E., now the Pharisees are on the other side of this extraordinarily consequential decision," says Chilton. "Paul attacks anyone who supports the widespread use of circumcision as being a hypocrite, a legalist and being cut off from Christ. And that's pretty much the take of the New Testament on the Pharisees. It seems that it was this internal dispute among Jesus' followers that produced this stark line of demarcation between Christians and Pharisees."

What's important to understand is that the four gospels of the New Testament (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John) were written starting in the year 70 C.E., decades after the meeting in Jerusalem. So it's very possible that Jesus himself wouldn't have harbored such distaste for the Pharisees during his lifetime, but that the authors of the New Testament wrote the gospels with a chip on their shoulder following their ugly divorce with the Pharisees over circumcision.

"The gospels are written from the point of view of a breach that hadn't occurred at the time of Jesus," says Chilton.

Advertisement

After the Second Temple was destroyed in 70 C.E., Chilton says that the power structure of Jewish religious life was toppled with it. The Sadducees, who had been the most influential force during the Second Temple period, were scattered, while the underdog Pharisees, "who had been very much on the outs," says Chilton, "really emerged as the last authority standing in Jewish history."

Over the ensuing centuries, the oral traditions of the Pharisees were committed to writing in the Mishnah and then commented upon in the Babylonian Talmud, becoming the basis for Rabbinic Judaism. The Pharisaic "sages" who had transmitted the oral tradition from the time of Moses were replaced by learned rabbis who studied the Torah and the complex commentaries found in the Talmud.

Advertisement

Modern Judaism is, in a sense, a continuation of the Hebrew word first championed by the Pharisees.

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

Advertisement