You've seen the headline dozens of times. A movie star or professional athlete gets fired for making an insulting or racist comment during a TV interview. The person's response: "Last time I checked, it's a free country!"

That's true. The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees the right to freedom of speech. But that doesn't mean that people won't be offended by your words or that the First Amendment protects the right to say anything, anywhere or anytime without repercussions.

Advertisement

The full text of the First Amendment reads:

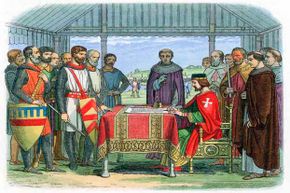

The Founding Fathers drafted the Constitution in 1787, but the states refused to ratify it without a Bill of Rights explicitly saying what the new government could and could not do. Recently freed from a tyrannical king, the American people wanted a limited government with strong protections for personal freedoms and political dissent [source: ACLU].

The Bill of Rights (which encapsulates the first 10 amendments to the Constitution) became law in 1791, but the broad freedoms outlined in the First Amendment have been refined by centuries of court rulings, including many historic Supreme Court decisions. America is still a "free country," but you might be surprised how many rights are absolutely not granted by the First Amendment.