A Right by Any Other Name ...

In order to understand the importance of the civil rights movement, you must first consider what civil rights are, exactly. You hear about certain civil rights all the time, such as freedom of speech. Some other civil rights are:

- Freedom from involuntary servitude

- Freedom of assembly

- The right to vote

- The right to fair and equal treatment in public places

When an individual is denied any of these civil rights based on his or her gender, race, religious beliefs or even age, it is considered discrimination. The government has created several statutes to counteract discriminatory practices. For example, Section 601 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 252, 42 U.S.C. 2000d, states:

No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.

This particular law affects many areas of life, but to give you a concrete example: This law ensures that students, no matter their gender, race, or religious creed, wanting to attend a public university (an institution that receives Federal financial assistance) are given fair consideration for admittance during the application process.

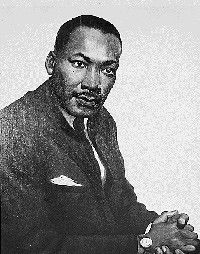

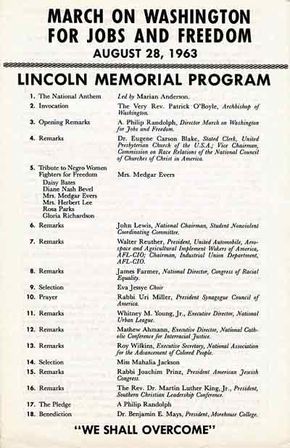

An Eddy of Change The 1950s and 1960s are considered the decades of the civil rights movement. It was during these decades that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. dedicated himself completely to the civil rights movement, human welfare, world peace and the struggle against poverty. In doing so, he faced countless arrests and unwarranted acts of violence, including bombs, a stoning and a stabbing.

The latter part of the 1960s saw a shift in King's focus, from civil rights to socioeconomic issues and peace. Though originally conceived in 1962, it was during the late 60s that "Operation Breadbasket" truly took flight, becoming a nationwide program. The goal of Operation Breadbasket, much like the Poor People's Campaign mentioned earlier, was improved economic conditions. In 1966, King asked his aide Jesse Jackson to head a Chicago division of Operation Breadbasket. Jackson soon found success when he garnered cooperation with various national companies that agreed to employ black workers and sell black-owned product lines.

King's philosophy on peace and his open opposition to the Vietnam War is clearly evident in this excerpt from his speech "Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution," given March 31, 1968, at the National Cathedral just days before his death:

Mankind must put an end to war or war will put an end to mankind -- and the best way to start is to put an end to war in Vietnam ... It is no longer a choice, my friends, between violence and nonviolence. It is either nonviolence or nonexistence. And the alternative to disarmament, the alternative to a greater suspension of nuclear tests, the alternative to strengthening the United Nations and thereby disarming the whole world, may well be a civilization plunged into the abyss of annihilation, and our earthly habitat would be transformed into an inferno that even the mind of Dante could not imagine.

For King, the early part of this decade was filled with activity, all of it culminating in two landmark events -- the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

On July 2nd, King stood nearby as President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Dr. King and scores of civil rights activists and supporters heard an answer to their collective call for justice in the new Act:

To enforce the constitutional right to vote, to confer jurisdiction upon the district courts of the United States to provide injunctive relief against discrimination in public accommodations, to authorize the Attorney General to institute suits to protect constitutional rights in public facilities and public education, to extend the Commission on Civil Rights, to prevent discrimination in federally assisted programs, to establish a Commission on Equal Employment Opportunity, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That this Act may be cited as the 'Civil Rights Act of 1964'."

Some of the precipitating events of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 are:

- June 1964 - Three young civil rights workers, Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney, are murdered in Mississippi. The three young men were in Mississippi to help with the registration of black voters.

- May 3, 1963 - A group of approximately 2,500 young, non-violent protestors are besieged by powerful fire hoses, dogs and club-carrying police. The turmoil that ensues makes national and international headlines complete with startling photos.

- April 16, 1963 - In response to a plea by white clergymen to stop protesting, Dr. King responds from his 11-day jail sentence in "Letter from Birmingham Jail": You deplore the demonstrations taking place in Birmingham. But your statement, I am sorry to say, fails to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about the demonstrations. I am sure that none of you would want to rest content with the superficial kind of social analysis that deals merely with effects and does not grapple with underlying causes. It is unfortunate that demonstrations are taking place in Birmingham, but it is even more unfortunate that the city's white power structure left the Negro community with no alternative.

- 1962 - President Kennedy orders federal marshals to escort James Meredith, the first black student to enroll at the University of Mississippi, to campus. A riot breaks out and two students are killed before the National Guard arrives to assist the marshals.

- King and other members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) launch the Birmingham campaign. During a series of meetings, Dr. King explains his belief in nonviolent resistance and submits a general call to action for volunteers for this campaign. His methods of resistance include marches on City Hall, a boycott of Birmingham merchants and sit-ins at local lunch counters.

In 1960, Dr. King resigned from his post as pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church and moved to Atlanta to devote himself fully to the civil rights movement. At this time, King had already been working for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) for three years. The SCLC was founded after the success of the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) in desegregating the Montgomery bus system.

In December of 1955, Rosa Parks, a 43-year-old black seamstress and secretary for the local NAACP chapter, refused to vacate her seat on a bus so that a white man could sit down. Subsequently, she was arrested. Responding to Parks' arrest, several community leaders, including Martin Luther King, Jr., organized the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The boycott continued, and in December of 1956, a little over one year after the boycott started, the United States Supreme Court declared Alabama's segregation laws unconstitutional. The Montgomery buses were desegregated. Dr. King's leadership of the boycott garnered him national attention.