The United Kingdom's National DNA Database (NDNAD) has been received with mounting criticism at each change. Many people have wondered why the government has not simply required everyone to submit a sample instead of slowly broadening its coverage to include more and more citizens. They call for more openness on the part of the government.

Parents, educators and many child behaviorists have been especially bothered by the suggestion that all children deemed to display behavioral problems or tendencies should have samples of their DNA put into the database. They feel that it is unfair to punish a child for something that he only might do, but has not yet done, and that inclusion into the database can only create a stigma and possibly cause problems for the child.

A representative of one British civil rights group, Liberty, pointed out that there is a disproportionate number of ethnic minorities in the database, which could lead to racial profiling. Specific socio-economic groups are already thought by many analysts to be more prone to violent crime; some critics argue that classification in a database could exacerbate the problem and reinforce stereotypes. The director of human rights watchdog group Privacy International, Simon Davies, said that it is "obscene" for the Metropolitan Police Homicide Prevention Units "to suggest there should be a 'crime idol' list of those who might commit an offence" [source: Bannerman].

Databases in the United States have also come under fire. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has blasted the continued expansions of DNA collection in the CODIS database, citing violations of citizens' right to privacy and the potential for institutionalized discrimination. They argue that DNA is very different from fingerprints in that it contains a vast amount of private information, including mental and physical defects and ancestry.

Every 10 years, census takers collect all kinds of information about the people living in the United States. This data is used for things like apportioning the correct number of seats in the House of Representatives, and it's not available to the public for 72 years after the data was taken. The Census Bureau is currently not allowed to reveal any identifiable information about the individuals they encounter. However, in the past the FBI has legally used census information to identify people. During World War II, it compiled a list of potential enemies of the state, which eventually resulted in the internment of Japanese-Americans. If a national future crime database were in the works, Congress could once again make census data minable by other law enforcement agencies in the name of safety.

Medical and mental health records are currently protected by state and federal privacy laws as well. Doctors and psychologists, for example, cannot release specific information about your condition without written consent from you -- for the most part. There are exceptions; a psychologist in California must break confidentiality if he suspects that you are a danger to yourself or others, or are abusing a child or elderly adult. A judge can also compel a psychologist by court order to speak about your treatment in the course of a trial.

Finally, assuming you have insurance coverage, your insurance company knows all about your various diagnoses. Again, there are privacy laws, but legislation could make all of this information available to law enforcement officials and analysts. The same goes for financial records and employment records.

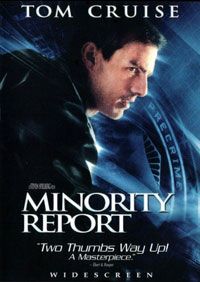

Concerned? Keep in mind that the "Minority Report" scenario is still a long way off (assuming we ever scientifically prove the validity of pre-cognition); more likely, a future crime database would be used to monitor and treat potential criminals rather than actually arrest them for as-yet-uncommitted crimes. A single drop of your blood could be enough to tell whether you're one of them.

For lots more information about crime and the long arm of the law, see the articles on the next page.