There are very few things more strongly associated with the darkest corners of the most remote jungles than shrunken heads. Probably only cannibalism is capable of evoking more dread and discomforting imagery, yet some anthropologists still dispute whether cannibalism was ever widely practiced as a custom in any culture. There is evidence that humans have, across the globe and at different times in history, eaten other humans. Yet, these instances may have taken place during times of extreme social stress, like famine. The jury is still out on the kind of cannibalism most people assume took place among indigenous tribes.

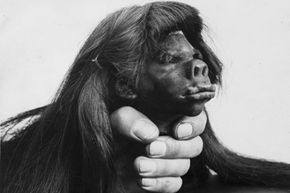

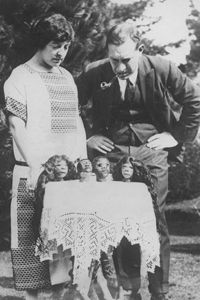

This is not the case with shrunken heads. Shrunken heads are an actuality. Ritual head shrinking is well known and widely documented -- you can visit them in museums around the world. And its practice isn't spread out across time and space: While groups from Europe, Oceana, North America and Africa have long taken the heads of enemies killed in battle, a single tribe, the Shuar, who live in a region of the Amazon basin that straddles Ecuador and Peru, are the only group known to shrink heads. They continued this practice until as recently as the 1950s.

Advertisement

Much of the world has long held a fearful image of the Shuar tribespeople. The idea of a person who, under the influence of hallucinogenic drugs, will drive a spear through your throat, cut your head from your body, and wear it, shrunken, is indeed fearsome. Beginning in 1599, the Shuar were one of the few groups to successfully repel and maintain freedom from colonial rule. In that year, the Shuar killed 25,000 colonists during a revolt. From then on, the tribe lived as it pleased in relative isolation from the rest of the world, warring with one another.

This isolation and the Shuar's practice of creating shrunken heads -- called tsantsas -- has given them a fearsome reputation with the rest of the world. Yet, as with any culture whose practices are viewed as gruesome to most other cultures, a deeper look reveals reasons and explanations that escape first notice. The Shuar shrink the heads of their dead enemies, yes, and such a ritual deserves a deeper look.

Advertisement