The Hague Conventions address not only armed conflict; the very first Hague law stresses peaceful settlement of disputes, going to great lengths to prevent war through very specific procedures intended to reach a diplomatic solution to any national and/or international disagreement. Arbitration, Committees of Inquiry, neutral mediators and what can be described as a 30-day "time out" are all called upon in order to avoid war. It is only once all of these steps have been exhausted that it is acceptable to declare war. And then, a formal declaration -- or an ultimatum indicating a formal declaration -- is necessary. An initial surprise attack is illegal.

Combat and Weaponry

The right of belligerents to adopt means of injuring the enemy is not unlimited. (Hague IV)

Many of the laws governing battle are fairly obvious: It is illegal to misuse a white flag, a symbol of surrender or truce (Hague IV); it is illegal to kill or injure a person who has surrendered; it is illegal to attack a defenseless person or place; it is illegal to attack a building that is being used as a hospital. Some of the rules, however, are less patent.

National and cultural symbols are protected. Armed forces may not use the enemy's flag, uniform or insignia, nor the symbol of the Red Cross, for their own purposes. The enemy's property is not to be taken or destroyed unless it's critical to military operations. Structures dedicated to art, science and charitable missions, as well as any historic or cultural objects, are off limits, unless, of course, they are being used for military operations. In that case, they're pretty much fair game.

In general, there is a ban on weapons whose purpose is to maximize pain and suffering: no poisoned weapons; no bullets that do additional damage once inside the body; no chemical or biological weapons.

Chemical and biological warfare is addressed by both the Hague and Geneva laws. Declaration II of The Hague Peace Conference made deadly gas attacks illegal back in 1899. The 1925 Geneva Protocol prohibited lethal gas and bacterial methods of warfare. The Geneva Convention of 1972 reiterated this prohibition by outlawing the "development, production and stockpiling" of these weapons and insisting on the elimination of any already in existence.

Genocide -- the systematic destruction of a particular group of people based on nationality or ethnicity -- is prohibited by a 1948 treaty dedicated solely to its prevention and the punishment of those who commit it.

Wounded or Sick Troops

In essence: If they're wounded or sick, HELP THEM! The first Geneva Convention addresses the issue of injured or otherwise debilitated troops (as well as medical personnel and chaplains), and takes the humanitarian stance that as soon as a soldier is no longer able to fight, that person ceases to be a target. And beyond that, there is a call to action: Regardless of which side the wounded individual was fighting for, medical attention must be given. This includes actively administering treatment and allowing the Red Cross to administer treatment.

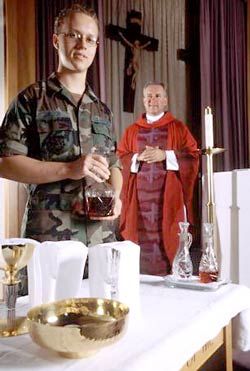

In the blanket protection of wounded or sick troops, medical personnel and chaplains, there is the assumption that these people are unarmed (or, in the case of troops, not able to use whatever arms they may have on them). In the case of medical personnel and chaplains, this raises the interesting paradox that these people are not actually prohibited from bearing arms in order to protect themselves; but if they do arm themselves, they give up certain aspects of their protected status. So in order to be fully protected from attack under the laws of war, they must be vulnerable to attack.

Sick or wounded troops must "in all circumstances be treated humanely, without any adverse distinction founded on race, colour, religion or faith, sex, birth or wealth, or any other similar criteria" (Geneva I). It is illegal to kill, mutilate, torture or perform "biological experiments" on a wounded or sick person. It is illegal to treat this person in a "humiliating and degrading" manner. It is illegal to hold this person hostage.

The Geneva Convention on the treatment of the wounded and sick discusses in detail the way to handle one of the most common aspects of war: death. The dead are to be collected, examined (only to be sure that the person is in fact dead), identified and properly buried. If necessary, fighting must be suspended in order for the dead to be recovered. The bodies must be treated with respect, and, if possible, buried according to their respective religions. Those who die in wartime have to receive the same treatment as those who die in peacetime. Communicating through a Graves Registration Service established at the onset of war, the location of the graves must be provided to the opposing force so that the bodies may be later exhumed and sent home, and all of the property found on the body must be returned to the next of kin.