Early History of Libertarianism

One of the central tenets of libertarianism is the belief in a "natural law" that exists independent of manmade laws. As early as the 6th century B.C., the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu argued, "Without law or compulsion, men would dwell in harmony" [source: Boaz].

In Western culture, ancient Roman and early Christian philosophers made a clear distinction between the natural law of God, or "the gods," and the law of man. When asked if his followers should pay taxes, Jesus declared, "Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's and unto God the things that are God's." Libertarian author David Boaz believes that this separation of church and state is essential to the development of civil society. Since neither the church nor the state has total control of individual choices, people are free to develop their own ideas of liberty.

Advertisement

Another central idea of libertarianism is a distrust of centralized power. In medieval Europe, power was held by a succession of unelected kings who owned all property, controlled all wealth, and could tax, confiscate and jail with impunity. During a momentous period from 1215 to 1222, three separate European societies imposed the world's first limits on authoritarian power [source: Boaz].

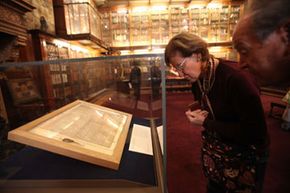

In England, the barons forced King John to sign the Magna Carta, giving unprecedented freedom from government interference and unfair taxation. Similar documents were signed in Germany and Hungary, each of them creating new rights for individuals and new autonomy for towns and boroughs. Perhaps most importantly, these documents cemented the idea that citizens — or at least the medieval class of noblemen — had the right to check or outright reject the actions of a tyrannical ruler.

The Renaissance furthered the cause of reason and individual rights over religious authority, and the protestant Reformation challenged the authority of a centralized Church aligned with the state. But despite these revolutionary events, much of Europe remained under the tight grip of despotic kings in France, England and elsewhere. A significant change came under the Glorious Revolution, when the throne of England was offered to William and Mary of Holland, who created the first Bill of Rights in 1689 [source: Boaz].

While this Bill of Rights has little in common with the Bill of Rights amending the United States Constitution, it opened the door for the school of political thought that would have a profound influence on the framers of the U.S. Constitution: a philosophy called "classical liberalism."