On April 4, 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. gave a speech to around 3,000 people at Riverside Church in Manhattan. In it, he advocated for an end to the Vietnam War, and he encouraged conscientious objection, or refusing to serve in the military based on moral or religious beliefs. "Every man of humane convictions must decide on the protest that best suits his convictions," King said, "but we must all protest."

King believed that protests have the power to catalyze change, and he held America accountable for upholding its principles of freedom of assembly, speech and the press. As Ralph Young, a history professor at Temple University, notes in his book "Dissent: The History of an American Idea," the United States was built on a foundation of resistance and transformation.

Advertisement

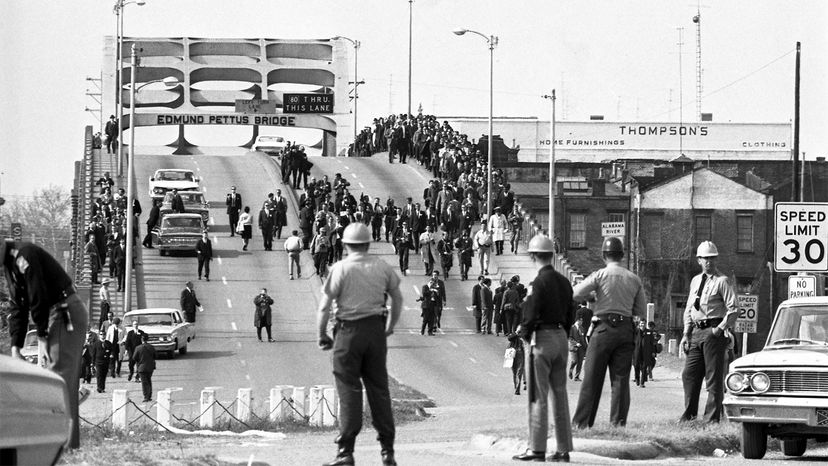

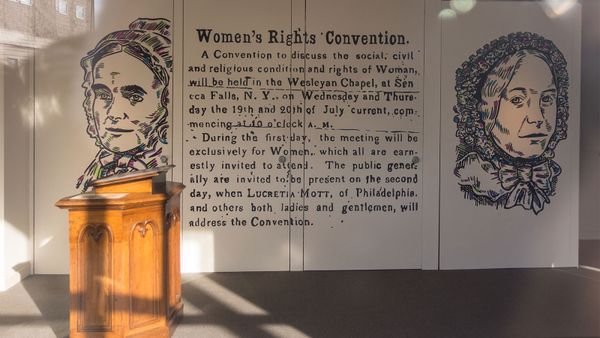

U.S. history is not a tale of quiet acceptance — insurgents, agitators and innovators played major roles in driving progress in the nation. But even when the process is difficult, the goal of protesting is simple: to raise awareness and sway policy or public opinion. "The main point is that the dissenters convince people that they have a legitimate grievance and that they force people to start considering which side they stand [on] in an issue," says Young.

Though all protests are not made equal, tactics like boycotts, marches and strikes can all be effective. Here are three protests that moved the needle in their favor.

Advertisement