Once upon a time in America, Christmas was not a big deal. It might be difficult to fathom now, when ads for chocolates and jewelry pop up before Thanksgiving, and decked-out trees appear in living rooms shortly after. In fact, Christmas used to be flat-out illegal.

When the Mayflower landed at what is now Cape Cod, Massachusetts, in 1620, the Pilgrims brought some serious baggage. They were aiming to establish a colony and a new way of life in the New World. One thing the Puritans wanted to leave behind: Christmas.

Advertisement

In England, as in much of Europe, Christmas was rife with unbridled partying. The harvests were done. The cattle were slaughtered so they wouldn't have to be fed in winter. That made fresh meat and fresh wine — as well as time to eat, drink and carry on — plentiful.

Puritans didn't buy into the idea of Christmas. The Bible notes no date for Jesus' birth. In the Puritan mind, then, there was nothing to celebrate.

"Christmastime had really gotten out of hand. What was going on in England, with the feasting and the gambling and the general debauchery, they took as a sign of the decline of civilization and a decline of all the things that they valued," says Penne Restad, a history professor at the University of Texas and author of the book "Christmas in America: A History." "So they were really positing this idea of not celebrating Christmas as an opposition to all the decay of English society."

They were so serious about treating Dec. 25 as just another day that everyone on the Mayflower — some, mind you, were not even Puritans — worked on the first Christmas Day in America.

They didn't get time-and-a-half, either.

Letting Loose ... Kind Of

The non-Puritans in the bunch were not as keen on a Christmas ban. Restad says it wasn't long before they acted out.

"Some of these newcomers refused to work ... one of those first Christmases," she says. "William Bradford [the English Separatist and early governor of Plymouth Colony] said, 'OK, that's fine, until you're better informed, that's OK.'"

"Apparently, they went out on the street — the word at the time was 'frolicking' — playing street games. He basically told them to take it indoors. [He said] 'I don't mind if you're doing this, but I don't want to see any of it. It sets a bad tone.' Those were not his exact words, incidentally."

Not all of America was so against the idea of celebrating Christmas. Settlements in the southern part of America, like the one in Jamestown, Virginia, let loose. But the Puritans kept a stranglehold on fun in New England.

The ban never was completely successful, though. From "The Battle for Christmas: A Social and Cultural History of Our Most Cherished Holiday," by Stephen Nissenbaum:

A changing society, though, would not be denied. From "Christmas in America: A History":

Even after the Colonies united and became a nation, years passed before Christmas became the holiday we know it as today. Congress was in session on Christmas Day 1789, the year after the Constitution was ratified. The Senate worked on Christmas Day 1797. The House met on Christmas Day in 1802.

Finally, Christmas

Christmas began to take its present form later in the 19th century. Different religions and denominations — Protestants and Catholics among them — emerged in America, and they held Christmas as both a holy day and a day of celebration. The Puritans noticed.

"[The Puritans] are sort of being introduced to varieties of religious experiences that can't help but start to kind of wear away one's commitment to a single way of thinking," Restad says. Different religions formed local governments, and trade between various networks helped calm the antipathies between the factions.

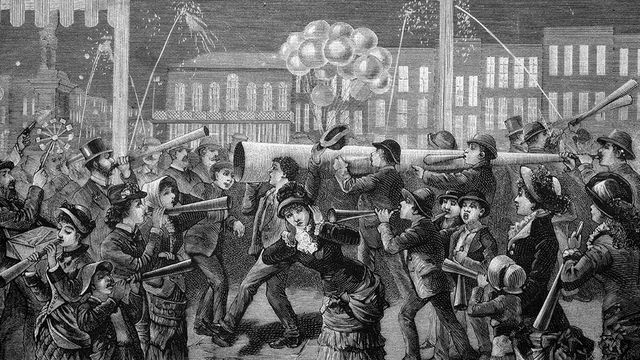

As the New World prospered and a middle class was born, the idea of giving and receiving Christmas gifts took hold. An emphasis on home and family followed, away from the "frolicking" in the street and the male-centered celebrations involving drinking, feasting and sex.

Finally, in 1870 — 250 years after the Puritans landed at Plymouth and put the squeeze on the idea of Christmas as a celebration — the U.S. declared Christmas a national holiday.

Ever since, celebrations big and small, secular and nonsecular, have marked the day.

Advertisement