In Taoism, chi refers to the living energy in all things. Kung is a term that refers to the achievements of long practice. Together, as chi kung, these words describe a relationship between someone who cultivates the chi and the discipline they use.

Every once in a long while, when walking along a fence bordering a field, you'll notice a single blade of hay protruding from both sides of a fence pole. Only a gust of wind traveling at the right speed and moving in the right direction could provide the precise amount of force to accomplish this feat.

Advertisement

Here nature reveals the power of chi in a quietly spectacular way. This power is the force that chi kung practitioners seek to cultivate.

The Horse Stance

As a combination of the concepts of chi and kung, chi kung exercises are used specifically to collect and store chi. One such exercise is The Horse Stance, which is known throughout traditional healing and martial arts circles, and it is recognized universally as an extremely beneficial exercise.

While there are many variations, the version described here is very basic. Although the posture itself is often found to be difficult and uncomfortable at first, these problems disappear with practice.

Usually, a series of special opening and closing movements are used in connection with The Horse, as it is sometimes called. These are designed to promote the movement of chi by opening and closing certain channels in the body, well-known to acupuncturists and other practitioners of traditional medicine. However, benefit can be derived simply by practicing The Horse by itself.

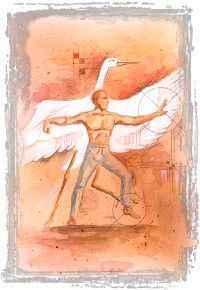

In a well-executed Horse Stance chi kung exercise, the shoulders and back muscles are completely relaxed throughout the exercise. The feet are placed firmly on the ground about shoulder-width apart.

In this form of the stance, the knees are bent slightly so that they are directly above the toes. The arms are raised slowly to waist level with the elbows kept close to the torso, which leans forward slightly.

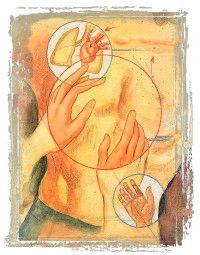

The elbows can be raised or lowered until a comfortable position is found. The exact height of the elbows has an influence on the way chi is absorbed into, and emitted from, the body. The two palms face earthward or sometimes face each other. This is the basic Horse Stance posture.

What is actually happening in the mind of the practitioner is this: The chi is envisioned as moving upward from the ground through the feet, the legs, and past the waist. It flows up along the spinal column, past the shoulders, and into the arms.

Then the chi moves past the elbows and out from the fingers. If the muscles or ligaments are tense in the hips or along the back and shoulders, the chi will be prevented from flowing, and there is no point in continuing the exercise. Practitioners will often step out of the stance until the muscles are once again relaxed.

When the chi begins to flow properly, the body begins to rock slowly back and forth, like a supple tree bending in a slight breeze. This is a sign of relaxation. Tense muscles prevent the chi from flowing along the channels.

Over time, this stance can be held comfortably for half an hour or more. While standing in The Horse Stance will strengthen the legs, this chi kung exercise also has the important function of promoting the flow of chi through the body.

Brought to North America by immigrating Asian chi kung masters and well-traveled Westerners with an interest in the subject, these techniques have remained essentially unchanged during their long migration.

This Horse Stance is the same basic posture used throughout chi kung history. Even though many variations in the basic stance have developed, the ideas discussed above are still in use today.

Continue reading to learn more about the origins of chi kung and the differences between certain styles of chi kung.

To learn more about chi and its relation to Taoism, see:

Advertisement