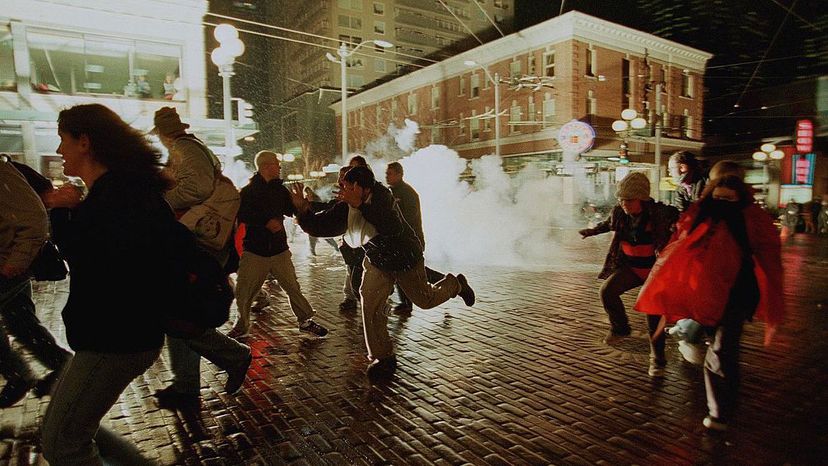

You may have seen TV footage of black-clad, masked protesters, smashing storefront windows and spray-painting their logo — an 'A' inside a circle — on buildings on the eve of President Donald Trump's inauguration in January 2017. Or, viewed news stories about similarly clad dissidents throwing rocks and firebombs at police in the streets of Portland, Oregon, as a May Day march for immigrant and workers' rights suddenly turned into a melee [sources: Stockman, Ryan].

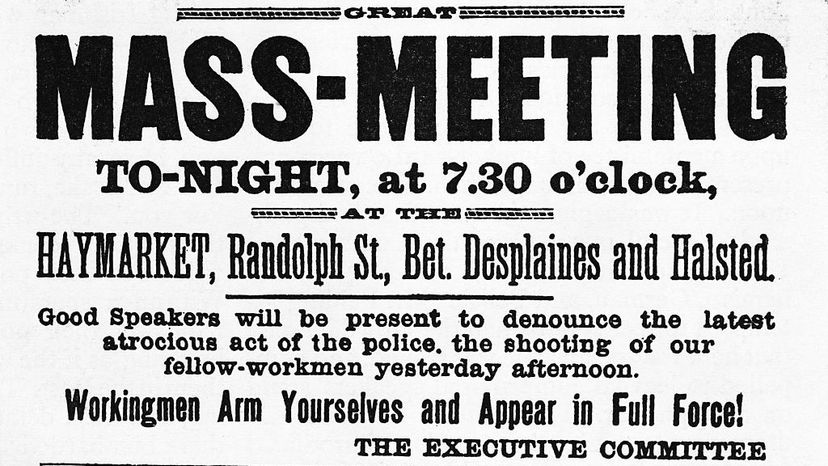

Those clashes — and countless others that have erupted over the years in cities across the U.S. and Europe — might give the impression that anarchists are simply out to create disorder and chaos. But there's a whole lot more to anarchism than that. It's a political philosophy that's been around since the mid-1800s and traces its roots back to ancient Greece and China, as well as to the ideas of thinkers such as Henry David Thoreau and Leo Tolstoy [sources: Woodcock, Buckley].

Advertisement

While there are a range of different ideas and approaches within the movement, in general anarchists believe that government authority — and any sort of hierarchy, for that matter — is bad for people and should be eliminated. They want to replace the existing power structure with a society in which everyone is free and equal, and the only associations are ones that people enter into voluntarily. Instead of electing representatives to lead them, people would rule themselves through direct democracy. As Robert Hoffman explained in the 1975 book "Anarchism as Political Philosophy," anarchists say "that a society ruled by government cannot be orderly, that government creates and perpetuates both disorder and violence."

But not all anarchists agree on the best way to establish a society without government authority. While some have depended on violent revolution as the only route, other anarchists have advocated achieving change peacefully, though activism and nonviolent protest. Some even have set up their own communities that practice anarchist principles on a local level, and in some places — most recently, in Greece — anarchists have stepped in to provide poor people with services when the government hasn't.

In this article, we'll look at the history of anarchism and the ways in which anarchists have tried to advance their vision of society.

Advertisement