If you want to get an up-close-and-personal understanding of American exceptionalism, just visit any small town or big city in the United States on the 4th of July.

On this day, Americans celebrate the adoption of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, the document by which the American colonies severed ties with the British Crown and laid forth certain "self-evident" truths that set apart the fledgling nation: "that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness."

Advertisement

Ask any American what they love about their country on July 4th, and no matter their political persuasion, they'll likely sum it up in one word: freedom. Freedom to exercise their religion, freedom to protest injustice, freedom from government intrusion or freedom to speak their mind.

For others, America is about opportunity. It's a place where the circumstances of your birth don't dictate the course of your life. Where individuals who work hard and remain optimistic can achieve any goal, whether it's owning a small business or being president of the United States.

And then there's the way that Americans celebrate the 4th of July, which points to some core aspects of American exceptionalism, including a few that rub other nations the wrong way.

On the 4th of July, America's blustery patriotism is on public display, with parades in the streets and flags adorning every building, lawn and oversized T-shirt. Refrains of "God Bless America" reinforce the notion of America as a divinely sanctioned land and people. Topping it all off are explosive and expensive fireworks displays, not-so-subtle nods to the military might that not only secures American freedom but solidifies its influence over the rest of the world.

In America's deeply divided political discourse, the term American exceptionalism is now wielded as a political weapon. Candidates from the right accuse their opponents of not "loving America" or of abandoning the unique attributes that make America "great" in a move toward "European-style" forms of government.

And candidates from the left insist that America's exceptionalism is born from its diversity and sense of equality and argue that policies that limit immigration or infringe on civil rights are themselves "un-American."

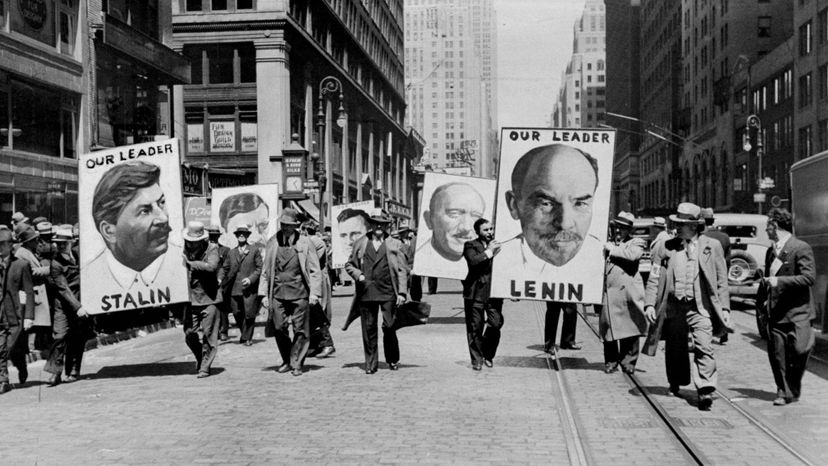

To get a better grasp on this slippery notion of American exceptionalism, we're going to dive into the double meaning of the term. We'll look at its surprising origins in communist theory, and the many ways that America's exceptionalism is a product of both factual differences between America and the rest of the world (metric system, anyone?), and simply the stories Americans like to tell about themselves.

Advertisement