The Evolution of the American Dream

By the time James Truslow Adams wrote his history of the United States in 1931 -- a book he had to be talked out of calling "The American Dream" -- he and many others believed the dream was in serious danger. A land that had once been viewed as the land of opportunity was now mired in the Great Depression. The Depression had destroyed the fortunes of legions of self-made millionaires and cost Americans of humbler means their homes and jobs, forcing them to live in hobo camps and beg for spare change on street corners. Few believed President Herbert Hoover's words that "prosperity was just around the corner" [source: Hartman].

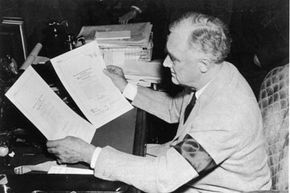

Hoover's successor, Franklin D. Roosevelt, however, launched an array of social programs to help the impoverished, and had better luck convincing Americans to believe they could improve their lots in life. In a January 1941 speech to Congress, Roosevelt articulated his own vision of a new, government-assisted American dream. This "dream" included full employment, government help for the elderly and those unable to work, and "enjoyment of the fruits of scientific progress in a wider and constantly rising standard of living" [source: Roosevelt].

Advertisement

That vision of boundless prosperity started to look real again after the end of World War II. Thanks to an economy primed by massive amounts of military spending, the victorious United States emerged as the wealthiest, most powerful -- and arguably, most envied --society on the planet. In the 1950s, Americans, who made up just six percent of the world's population, produced and consumed one-third of its goods and services. Factories busily churned out products to meet the needs of an exploding population, wages rose, and increasingly affluent workers and their growing families moved into spacious new houses in the suburbs [source: Schultz].

Many Americans in this new middle class embraced a belief in seemingly perpetual upward mobility. They believed that if they worked hard enough, life would continue to get better and better for them and for their offspring. To be sure, some social critics saw that dream as overly materialistic, spiritually empty, intellectually stifling and destructive. Others pointed out the fact that America wasn't necessarily a land of opportunity for everyone, particularly those who belonged to racial and ethnic minorities. We'll discuss these doubts further on the next page.