Key Takeaways

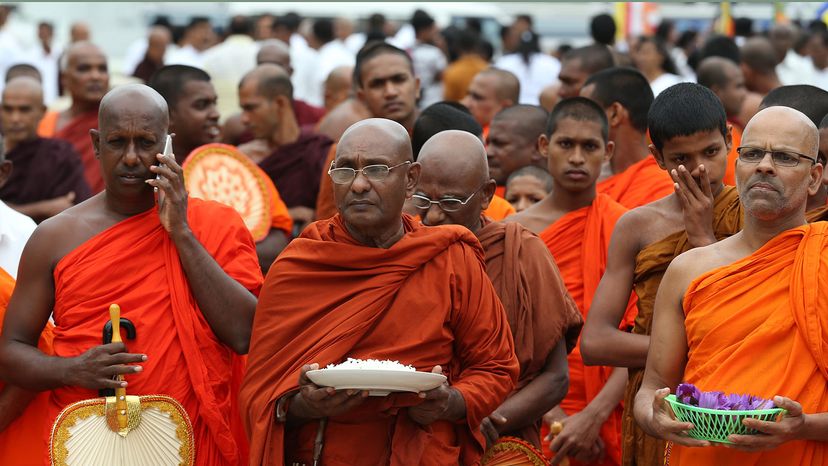

- Buddhism is not a homogenous group; some Buddhists are pacifists and vegetarians, while others may eat meat and engage in warfare.

- The Buddha taught against harming sentient beings, but traditional Theravada monks and lay followers are allowed to eat meat as part of their practice.

- While some Buddhists are pacifists, there have been instances of Buddhists engaging in warfare throughout history.

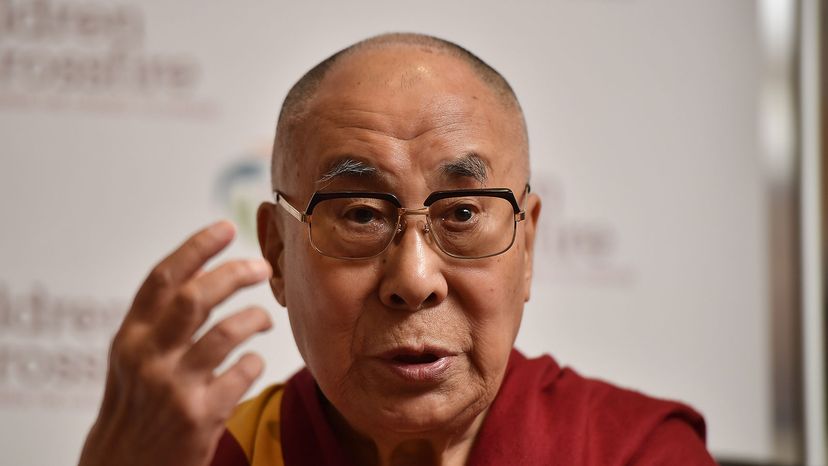

About 99 percent of the world's nearly 500 million Buddhists live in the Asia-Pacific region [source: Pew]. But that doesn't mean people in the West don't know anything about Buddhism. Perhaps they've heard of it through certain celebrities who are adherents, or from a yoga teacher who spent three weeks in Nepal and keeps talking about "mindfulness." Maybe they've seen the Dalai Lama on TV. They may even think the chubby smiling statue at the local Chinese restaurant represents Buddha (hint: it doesn't).

A 2015 report from the Pew Research Center projected the number of Buddhists worldwide to increase to 511 million by 2030, but with the worldwide population increase, the percentage of people who are Buddhists will actually decline from 7.1 percent to 6.1 percent. In North America, the percentage of people who are Buddhists is expected to increase from 0.8 percent in 2010 to 1.2 percent by 2050. Buddhists make up a tiny fraction of America's religious landscape, registering at 1 percent or less of the population in every state except California (2 percent) and Hawaii (8 percent) in 2015 [source: Pew].

Advertisement

So, while people in the West may think they know what Buddhism is all about, chances are they don't. We've assembled 10 questions and answers to clear up the confusion about one of the world's oldest and most influential religious traditions. Let's get started with a quick bio of the Buddha himself.