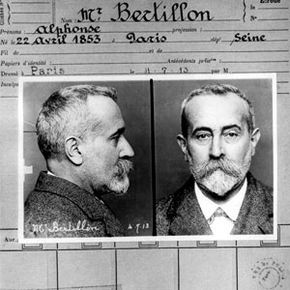

In the 1880s, French criminologist Alphonse Bertillon developed a particular obsession with itemizing physical characteristics of prisoners brought in to the Paris police station where he started out as a records clerk [source: National Library of Medicine]. Bertillon painstakingly measured prisoners' arm lengths, head circumferences, ear formations and other anatomical markers; made notes of tattoos and scars; and photographed their facial frontals and profiles. As he amassed this data, Bertillon developed a novel system for identifying inmates, which became known as criminal anthropometry. After French police used Bertillon's identification practices to nab 241 repeat offenders in 1884 alone, this early forensics science spread to other police departments around Europe and the United States [source: National Library of Medicine]. Today, one of the most commonly employed anthropometry tactics that hasn't changed all that much during the intervening century is the police sketch.

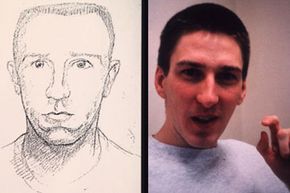

The FBI cites an eye witness sketch of Timothy McVeigh as a crucial piece of evidence that eventually brought the mastermind of the Oklahoma City bombing to justice. Ten hours after the 1995 explosion at the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building that killed 168 people, a forensic artist with the FBI's Investigative and Prosecutive Graphic Unit sketched out the perpetrator's face based on interviews with people who had spotted McVeigh in Junction City, Kan. renting a truck that was later found at the crime scene [source: FBI]. Having seen that relatively rudimentary FBI sketch, Oklahoma State Troopers who later arrested McVeigh on driving- and weapon-related charges unrelated to the bombing didn't release their suspicious-looking prisoner from jail.

Advertisement

Although the McVeigh case is an extraordinary example of a suspect sketch helping successfully nab a criminal on the lam, police sketches are nevertheless a routine part of law enforcement investigations. A forensic artist, who might double as a patrol officer or serve as a civilian contractor, usually interviews crime scene witnesses and victims about a perpetrator's appearance to create a composite sketch. The composite could be drawn completely by hand or computer generated. Sometimes, forensic artists use a combination of the two methods.

But no matter how fine-tuned the police sketch methodology, the most crucial component of an accurate facial composite is an eye witness' memory. Describing the face of someone who might have fled a crime scene or inflicted bodily harm on you might be an erroneous process. The human memory can play tricks, erasing certain details and amplifying others, for instance giving someone a beard when he had a mustache or a square jaw when it was actually rounded [source: Raeburn]. And for that reason, forensic artists must conduct preliminary interviews carefully and with sensitivity to elicit as many precise facial details as possible.

Advertisement