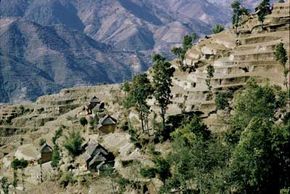

If you lay a map of Nepal's roads beside a map of its terrain, you'll notice a stark difference. Nepal's road map looks like a few lonely rivulets cutting through a barren landscape -- no spider web of intersecting road lines snake this country. But a topographical map reveals a completely different and much more dramatic image. The map virtually explodes with the craggy grandeur of the Himalayan mountains.

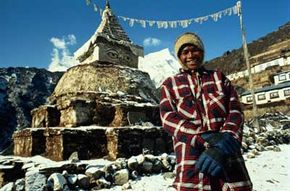

It is to those highest points of Nepal's geography that the Sherpa people migrated more than 500 years ago from Tibet. Famous for their domestic backdrop of Mount Everest, the tallest mountain in the world, Sherpas have developed a fascinating culture and livelihood interwoven with the perilous peaks among which they dwell. Likewise, where the world sees a geographical obstacle to overcome, Sherpas see a life source.

Advertisement

Sherpa literally means "people of the East" because they came from eastern Tibet. In the northeastern corner of Nepal, they settled in the Solu-Khumbu region at the southern base of Mount Everest, near the Dodh Koshi River fed by Himalayan glaciers. Here, they established multiple villages, home to around 25,000 people.

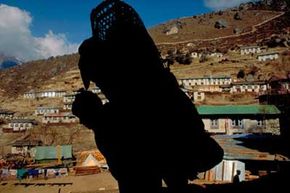

Until the influx of British settlers occurred in neighboring India in the early 20th century, Sherpas remained relatively isolated and unknown to the rest of the world. Then, with the first successful ascent of Mount Everest in 1953 by Edmund Hillary and a Sherpa named Tenzing Norgay, the Sherpa people and their seemingly natural ability to brave the staggering heights were thrown into the international spotlight. Tourists typically characterize them as hardy, friendly mountain guides and assistants who are incredibly strong and physically compact.

Yet, as we'll learn in this article, there's much more to the Sherpa culture than climbing. In fact, summiting Mount Everest is an afterthought for most of them, despite the personal glory some have earned.

But if Sherpa life isn't all about mountaineering, what is it like to live in the shadows of the Himalayas? Read on to discover the many intricacies of the Sherpa culture and the role Mount Everest plays, aside from the tourist draw.

Advertisement