In the 1930s, Leonard Keeler -- one of the men who developed what we recognize today as the modern polygraph -- marketed "The Magic Lie Detector," a tool used during interrogations [source: Larson]. The appeal of the technology, which can give an interrogator insight in the truthfulness of a suspect's tale, caught on quickly. Since then, history has proven that the polygraph isn't very magical, neither in its machinations, nor in the validity of its results.

MRI Image Gallery

The polygraph uses a combination of physiological measurements -- like blood pressure, heart rate and skin temperature -- to determine whether a person may be lying during a series of questions. The data rendered by the test is analyzed afterward to determine whether the person questioned exhibited signs of stress, an indication of deception.

Advertisement

But there's a two-sided problem with the polygraph that has become increasingly clear over the course of the past century: A person who can remain cool under pressure can beat a polygraph, and conversely, a person who doesn't handle stressful situations well may be inaccurately labeled a liar.

Due to the perceived threat of terrorism that was born out of the Sept. 11 attacks, the U.S. government decided that a better, more reliable way of determining truth was needed. It appears that MRI technology has emerged to fill the void created by a convergence of the lack of faith in polygraphs and the urgency to know friend from foe following Sept. 11.

MRI -- magnetic resonance imaging -- is a technology that has been in ever-increasing use since the first model was built by Raymond Damadian and his colleagues in 1976. As recently as just over 100 years ago, physicians routinely paid grave robbers to steal bodies for their use as cadavers. It was dissection of these cadavers that helped expand our working knowledge of human anatomy. X-ray photographs were the next big leap in this field of study, providing us a view into the human body without needless incision.

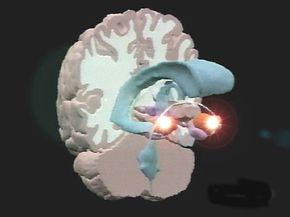

Now, MRI has revolutionized the field of anatomical study. Rather than investigating the inner workings of the human body through observation of dead organs or examining flat, cloudy images of bone and tissue, MRI allows radiologists to see real-time, 3-D models of human parts.

MRIs use powerful magnets to charge hydrogen protons within cells. A radio frequency is broadcast at these protons, which absorb the frequency and reflect it back at a receiver. This information is translated into an image of the area scanned. Through this method, MRIs have determined the exact location and size of tumors and mapped the extent of a stroke -- all before scalpel was ever put to skin. In these ways and many others, this technology has saved lives.

But thanks to some emerging research, it's becoming clear that an MRI could also serve a non-clinical purpose -- as a lie detector. Read on to find out how MRIs work as lie detectors and why some people are opposed to this use.

Advertisement