Key Takeaways

- The "hobo code" was a secret, symbol-based system used by Depression-era itinerant workers to share information.

- The pictographic code included directional symbols, danger warnings and tips on finding food and shelter.

- While evidence of widespread use is lacking, hobo monikers and symbols have been found, reflecting their resilience.

Think of it as a fringe culture emoji and hashtag moment that emerged and played out during the way-before-social-media-times of the post-Civil War railroad construction era and lasted well through the Great Depression. Think of it as enciphered hieroglyphics doodled in America's margins by down-and-out train surfers to other down-and-out train surfers. Think of it as a form of graffiti that's sometimes called hoboglyphs. Heck, why not just think of it as (copyright!) hoboji?

Hoboes were a widely displaced brotherhood (and sisterhood) of Depression-era itinerant workers who illegally hopped trains and journeyed across the country taking odd jobs wherever they could find them. Never staying in one place for very long, hobo lore suggests that during their cross-country travels hoboes developed a secret symbol-based system for sharing information with one another about, say, where to find a paying gig, which roads were good or bad to follow, or what potential dangers or hostilities (like police or railroad bulls) lurked up ahead.

Advertisement

Given the overwhelming challenges of surreptitiously train-hopping and the unpredictability of individual circumstances, the code was purportedly devised as an easy-to-understand, universal hobo language that helped fellow hoboes keep one another safe.

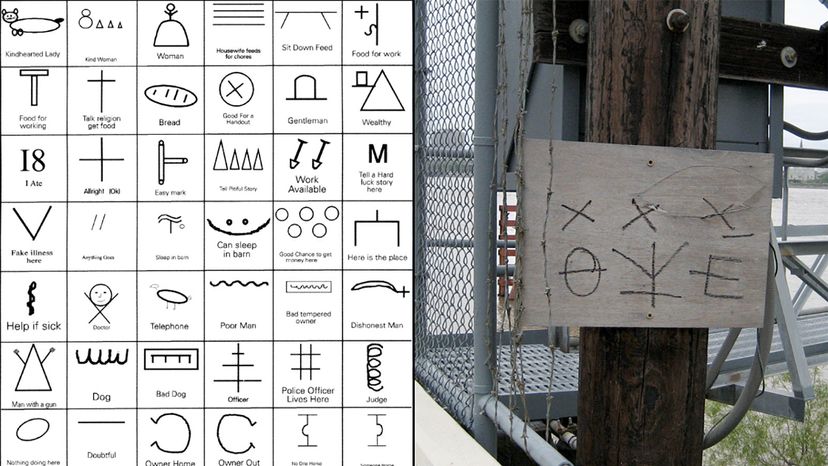

The pictographic code contains several elements that appear in more than one symbol, like the circles and arrows that comprise the directional symbols. Hash marks or crossed lines generally depict some form of danger, whereas a curly line inside a circle meant that there was a courthouse or police station nearby. Other hoboglyphs were easier to decipher — a cross meant that there was a church in the vicinity and the possibility of scoring a free meal and perhaps shelter for the night.

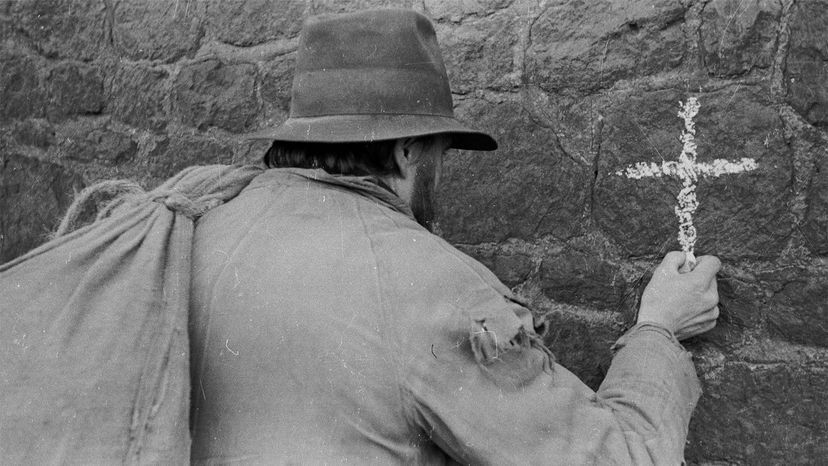

The story goes that hoboes typically tagged tree trunks or scrawled impermanent coded messages in chalk, charcoal or grease pencil in boxcars, under bridges, on water tower bases, walls, fences, sewer trestles and other surfaces in or near railroad yards where other hoboes were likely to pass by. Yet there remains little concrete anthropological evidence that the code was actually widely used. Which begs the question: If a hobo draws a symbol in chalk or charcoal and the rain washes it away, did the hobo ever exist in first place?

Some scholars believe hoboes communicated mostly by word-of-mouth — suggesting that homes, churches, dwellings or businesses frequented by hoboes were called upon quite logically because of their proximity to railroad tracks or railway stations — not because of any clandestine signage scribbled in code. To which a scholarly hobo might respond: Hmmm, or maybe the fact that no tangible evidence remains is a testament to the efficacy of the code? After all, any seasoned, self-respecting hobo 100 percent meant to get in and out of town without leaving a trace. Isn’t that kind of the point?

Thing is, the notion of the code came from hoboes themselves — an underground community that took great pride in being cagey and ambiguous.

Here's just a smattering of the hieroglyphic phrases supposedly known only to members of that notoriously unsung and elusive tribe known as the American hobo:

A kind lady lives here. Religious talk will get you food. Beware of bad man or mean dog. It's safe to camp here. Look out for hostile railroad detectives here. The jail in this town is rat infested and unsanitary. This is a good place to catch a train. Get out of this town as quickly as possible.

The lore of the hobo code seems to have originated with Leon Ray Livingston, better known as A-No. 1, America's self-proclaimed "most famous tramp who traveled 500,000 miles (804,672 kilometers) for $7.61." Livingston expounded the use of the hobo code to a variety of newspapers as he traveled throughout the country and published the code in his 1911 book entitled "Hobo Campfire Tales." It's important to note that his books are generally considered to be wildly exaggerated stories grounded in mere kernels of truth.

Preferring to remain as invisible as possible, hoboes used monikers, like A-No. 1, Ramblin' Jack, Illinois Slim, Mississippi Mike, Skysail Jack— insider nicknames that kept them anonymous and under the radar, yet said something about who they were, where they were going and where they'd been. While there may be little evidence to prove that the hobo code was actually widely used, we know for certain that hoboes left their marks. Anthropologists have found many examples of emblazoned hobo monikers, including a recent discovery of one by the hobo king himself.

Think of the hobo code symbols as abstract faces in a crowd of more than two million out-of-work laborers who rode the rails to survive a seriously harsh blip in American history. Think of each mark or moniker they left behind as their way of saying, “I was here. I pulled up my bootstraps. I existed.”

FAQs

How did hoboes typically communicate with each other?

Hoboes communicated with each other through a secret, symbol-based system known as the hobo code, which included pictographic symbols to share information.

Were there any specific rules or guidelines for creating hobo code symbols?

There were no specific rules for creating hobo code symbols, but common elements like circles and arrows were used for directional symbols, while hash marks or crossed lines generally depicted danger.

Advertisement