Back in the 1790s, America's founding father Alexander Hamilton said that "the true principle of a republic is, that the people should choose whom they please to govern them" [source: Whitaker]. That statement embodies what is supposed to be one of the strengths of American-style democracy — that all Americans are equal, and that each citizen has an equal say at the ballot box in choosing their elected representatives.

But that's not happening in Wisconsin, according to the Democratic plaintiffs in Gill v. Whitford, a case heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in October 2017. They argued that Republicans who control that state's legislature have unfairly rigged the system to hold on to power, even though Democrats have won a majority of the votes cast statewide for the Assembly, the legislature's lower house, in the last three straight elections [source: Wines].

Advertisement

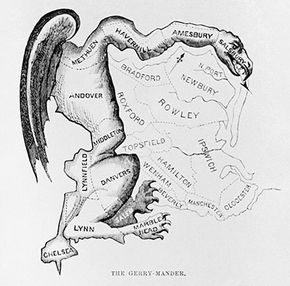

You may be wondering: But how could a party manage to hold the majority of legislative seats if they don't get a majority of the votes? All it takes is a little gerrymandering. That's the political trick of manipulating the size and shape of electoral districts, in order to give one party an advantage over its opposition [source: Donnelly].

Gerrymandering dates back to the very beginnings of the U.S., and it's been employed throughout the years to distort the political process and prevent opposition parties from challenging those in power. Gerrymandering can be occur in state legislative districts, but it also can be used to enable one party to dominate a state's congressional delegation as well.

A 2017 report by the Brennan Center for Justice calculated that in the 26 most populous states that account for 85 percent of congressional districts, Republicans managed to net 16 or 17 seats in the 2016 congressional elections because of partisan bias in the redistricting process. That's a big slice of the 24 seats that Democrats would need to flip in order to gain control of the House in the 2018 election. The report also said that almost all the gerrymandered districts reside in just seven states: Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Florida, Ohio, Texas and Virginia [source: Royden and Li].

In June 2018, the Supreme Court dismissed Gill v. Whitford, saying that the plaintiffs lacked standing and did not rule on the case's merits. The case was sent back to a lower court [source: Associated Press]. Had the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court decision throwing out Wisconsin's legislative map, it would have sent shockwaves through American politics, possibly invalidating districting schemes in 20 other states as well [sources: Wines, Ellenberg]. Though gerrymandering seems aimed at subverting democracy, the courts have pretty much allowed it over the years, unless it's been used for purposes of racial discrimination.

In June 2019, the Supreme Court went even further and, in a 5-4 vote along ideological lines (Rucho vs. Common Cause) ruled that "partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts" — meaning that federal judges should not second-guess lawmakers' decisions.

In this article, we'll explore the history of gerrymandering, why it has become so prevalent and so extreme, and how it interferes with voters' opportunity to be fairly represented in Congress. We'll also look at possible solutions to the problem. But first, here's a basic explanation of why gerrymandering is able to take place.

Advertisement