It was April 2016, and in a hearing room in Washington, D.C., an assortment of Valeant Pharmaceuticals officials each took their turn sitting in the hot seat, enduring a barrage of questions from U.S. senators about the company's practice of buying existing drugs and dramatically raising their prices. One executive admitted that Valeant had made "mistakes." But the senators weren't much moved by the witness's contrition. Sen. Claire McCaskill, D-Mo., angrily denounced the company and its practices. "It's immoral," she proclaimed. "It hurts real people, and it makes Americans very, very angry" [sources: Thomas, Koons and Edney].

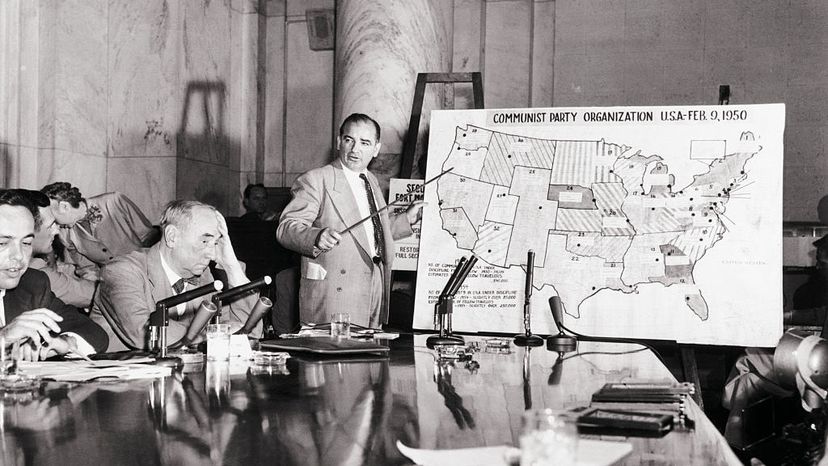

The Senate probe of pharmaceuticals pricing was just one of many such dramas that have played out on Capitol Hill. Since 1792, when the U.S. House passed a resolution calling for a probe into a disastrous military expedition against the Indians in the Northwest Territory, members of Congress have conducted scores of investigations on alleged wrongdoing and/or mistakes of various sorts.

Advertisement

Many of the probes — including some of the famous ones, such as the Watergate hearings of the mid-1970s — involve actions of the executive branch, in keeping with Congress's role as a check-and-balance against presidential power. But legislators have investigated plenty of problems and controversies in the private sector as well, ranging from the sinking of the Titanic in 1912 and rigged television quiz shows in the 1950s to the use of steroids and other performance-enhancing substances in Major League Baseball in the mid-2000s.

How does Congress decide what to investigate, and how does it go about doing it? What tangible impacts do all these probes have? How much of it is about solving problems, and how much is just grandstanding for political purposes? In this article, we'll try to answer all those questions, and more.

Advertisement