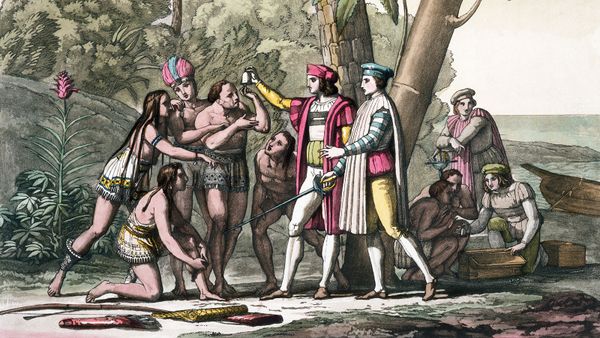

Accused of crimes ranging from slave-trading to genocide of indigenous peoples, Christopher Columbus has lost favor with many Americans. In 1977, just five years after Columbus Day became a national holiday in the U.S., participants at the United Nations International Conference on Discrimination against Indigenous Populations in the Americas proposed Indigenous Peoples Day as a replacement.

It took some years to catch on. In 1990, South Dakota became the first state to ditch Columbus Day for a holiday honoring Native Americans, and in 1992, the famously progressive city of Berkeley, California became the first to celebrate Indigenous Peoples Day in protest of the 500th anniversary of Columbus' arrival in the New World.

Advertisement

Now, at least 14 states (plus Washington, D.C.) and more than 130 American cities have either dropped Columbus Day entirely or co-celebrate Indigenous Peoples Day on the second Monday in October. (Hawaii calls it Discoverers Day and honors the Polynesian discoverers of Hawaii.) In 2021, President Joe Biden issued a proclamation recognizing Indigenous Peoples Day alongside Columbus Day. It was the first time a U.S. president had commemorated Indigenous Peoples Day.

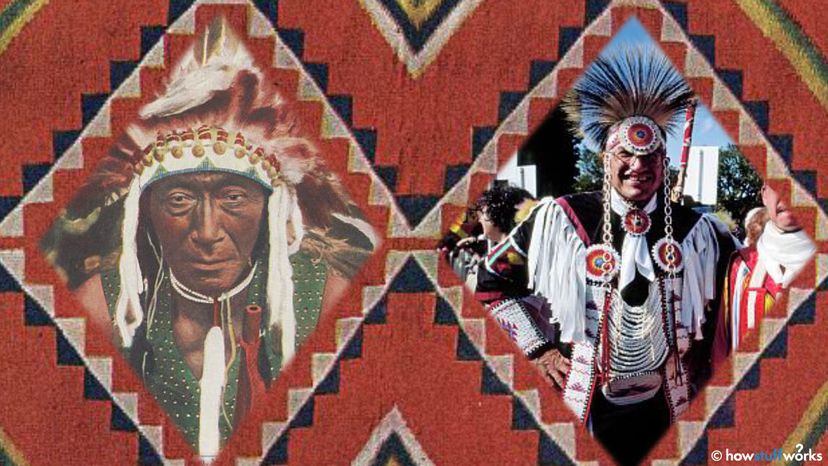

But what is Indigenous Peoples Day exactly, and how can Americans both honor the troubled history of the continent's original inhabitants while celebrating the living culture and contributions of modern Native Americans?

We spoke with Reneé Gokey, an education specialist at the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., about the opportunity that Indigenous Peoples Day gives all Americans to not only take an honest look at Native American history, but also to celebrate today's diverse Native cultures through their art, literature, film and food. (Gokey is an enrolled member of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma and is also Shawnee, Sac and Fox Nation, and Myaamia from her paternal grandparents.) Here are some of her suggestions:

Look for Histories That Includes Native Voices

Growing up, many Americans learned about Native Americans only in history class. Starting with Columbus, history lessons in school typically took on a Eurocentric perspective of "discovery" and Manifest Destiny, not the violent colonization and forced removal experienced by Native peoples.

One of Gokey's projects at the National Museum of the American Indian is Native Knowledge 360°, an interactive educational resource for teachers and students that explores key moments in U.S. history from an indigenous perspective. For example, what does it mean to remove a people? Or were treaties meant to last forever?

"Teaching more accurate and complete narratives that include these different perspectives is key to rethinking our history," says Gokey. "But we rarely hear Native perspectives in media, classrooms and books. The silences speak loudly and they really discount the incredible resilience and innovation of Native cultures."

Advertisement