You know the image of a standard American, usually Christian, funeral: It takes place at a funeral home with attendees dressed in all black. An open casket with an embalmed body rests in front of the crowd. After the service, a hearse takes the casket to a cemetery for burial.

This was a conventional funeral in the 1960s, but this send-off of the dead has undergone adjustments over the decades.

Advertisement

Perhaps the most significant change is the rising popularity of cremation, says Gary Laderman, chair of Emory University's department of religion and author of two books on death including "Rest in Peace: A Cultural History of Death and the Funeral Home in Twentieth-Century America."

The funeral industry had long worked to convince people of the importance of physically preserving loved ones, therefore burial remained prevalent.

"It's historically rooted in American culture, that is the idea that we can preserve the body," Laderman says. "That's an important concept in how we respond to and think about death."

But the idea of preserving the body started changing with the publication of a seminal book: Jessica Mitford's "The American Way of Death," a 1963 bestselling exposé of abuses in the U.S. funeral home industry. Laderman says Mitford's book ignited cremation because it provided alternative ideas to consumers.

In the 1960s, the cremation rate was only 3 percent, but today, cremations outpace burials. In 2017, the U.S. cremation rate was 51.6 percent, according to the Cremation Association of North America. By 2022, the rate is projected to jump by more than 6 percentage points.

Cremation has raised questions about the importance of the body and its role in funerals, Laderman says.

"Clearly, the idea that somehow the body needs to be preserved for all time in a casket in a vault with an embalmed body no longer holds," he says. "We have different ideas about symbolic, religious meanings of the body."

Mitford's exposé isn't the only reason for changing funeral norms. The 1960s were a time of cultural upheaval, which extended to analyzing accepted death customs.

"It's also in tandem with the whole spirit of the 1960s, challenging authority, new forms of spirituality, new ways of thinking about the afterlife, all these things in addition to the politics," Laderman says. "That too contributes to a real major shift in people's thinking about death, how they experience death and what they do with the corpse."

Consumer culture has shifted since the 1960s, allowing people more opportunities for customization according to tastes. "This also spills into how we treat our dead," Laderman says.

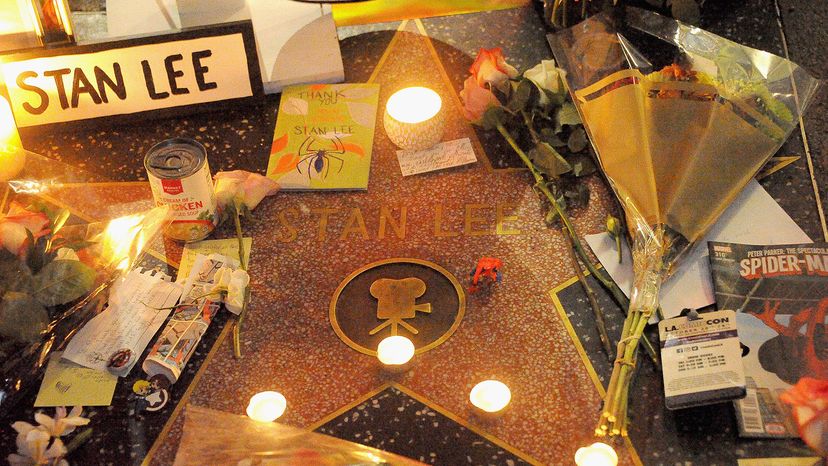

You might recognize this in the myriad ways that funerals have gotten personalized: requests for mourners to wear nonblack clothes, music liked by the deceased playing at funerals, tombstones that pay homage to the person's hobbies.

"It's just an increasing willingness within the funeral industry as well as other resources that are available to help people when they're dealing with loss that allows people to try to personalize this significant ritual moment after death and trying to figure out the best way to memorialize and, on a more crass level, do right by the dead," Laderman says.

More often, people don't even need to contemplate how to do right by the dead. Until the 1960s, people might include funeral recommendations in their will, but it didn't usually get any more specific. Now, people have gotten more comfortable with planning their own funerals. This further drives the trend toward personalization, Laderman says.

Organized religion's lessening influence has also taken its toll on funerals. Unaffiliated religious "nones" – people who are atheist, agnostic or "nothing in particular" – accounted for about 23 percent of U.S. adults, according to a Pew Research Center study in 2014. In 2007, only 16 percent of people were "nones."

"Traditionally, religion was the primary resource, providing all these cultural scripts for what to do with the body and the grave and what is the afterlife," Laderman says. "This is religion's business."

But traditional religions began losing their grip after the 1960s, which has created more freedom to choose other styles of funeral – another opportunity for personalization.

"To me, it's not a symptom of secularization or religion is absent," Laderman says. "It's kind of new forms of religious expression that get bound up in the most religious moment for any of us, which is when we have to face death."

Even the terminology of funerals has changed over the past decades, he says. It used to be called a "funeral service," but that morphed into "memorial service" and finally a "celebration of life" meant to showcase the deceased's life, personality, hobbies and accomplishments.

"[It] is a life-oriented mentality or attitude. It's not dwelling on the loss or the grief. It's not dwelling on the afterlife," Laderman says. "This celebration of life is something about an American effort — the optimism of really glorifying the person as they were when they were alive again as opposed to something about heaven or presence of God."

Advertisement