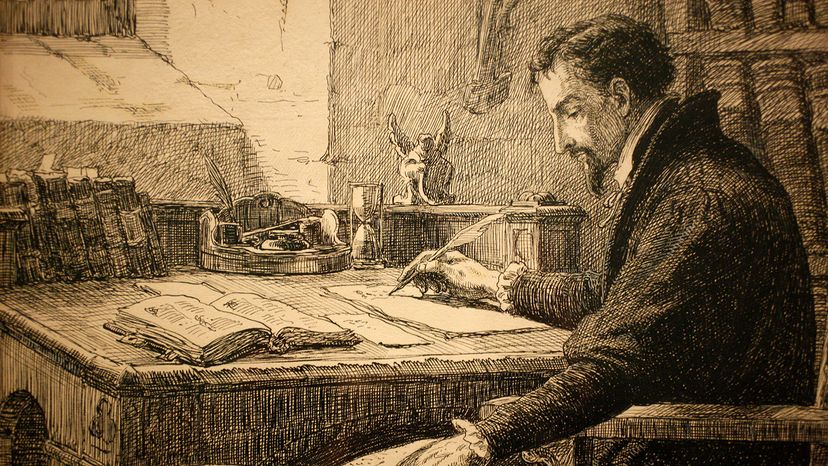

In 1536, a 27-year-old Jean Calvin (better known as John Calvin) fled his native France, where he had been persecuted for his newfound Protestant faith, and written a groundbreaking theological treatise titled "Institutes of the Christian Religion."

A wanted man in Catholic France, Calvin sought refuge in neighboring Switzerland, and stopped at an inn in Geneva where he planned to spend just one night. But when local church leader William Farel learned that the author of "Institutes" was there, he stormed into the inn and told Calvin that it was God's will that he stay and preach in Geneva.

Advertisement

When Calvin tried to explain that he was a scholar, not a preacher, Farel turned red in the face (not hard for a redhead) and swore an oath that God would curse Calvin's so-called "studies" if he dared to leave Geneva. A man of great faith, Calvin took this as a sign.

"I felt as if God from heaven had laid his mighty hand upon me to stop me in my course," Calvin later wrote, "and I was so terror stricken that I did not continue my journey."

John Calvin spent the rest of his life in Geneva preaching a new strain of Protestantism known as Reformed Theology. A contemporary of famed Reformation leader Martin Luther, Calvin was the father of Calvinism, a faith that's inextricably tied to the controversial doctrine of predestination, which holds that a sovereign God has already selected who will be saved and who will be damned.

To better understand the life and legacy of Calvin — one of the most influential and controversial figures in Christianity — we spoke with Bruce Gordon, a professor of ecclesiastical history at the Yale Divinity School and author of the biography "Calvin" and "John Calvin's Institutes of the Christian Religion: A Biography."

Advertisement