Gun violence in America has exploded since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the victims of deadly shootings are disproportionately young and Black.

In 2020, for the first time ever, firearm deaths outpaced automobile accidents as the leading cause of death among children 1 to 19 years of age, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And Black teens are the hardest hit. Of all Black teenagers (15-19) who died in 2020, more than half were victims of gun violence, according to a 2022 report from the John Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions.

Advertisement

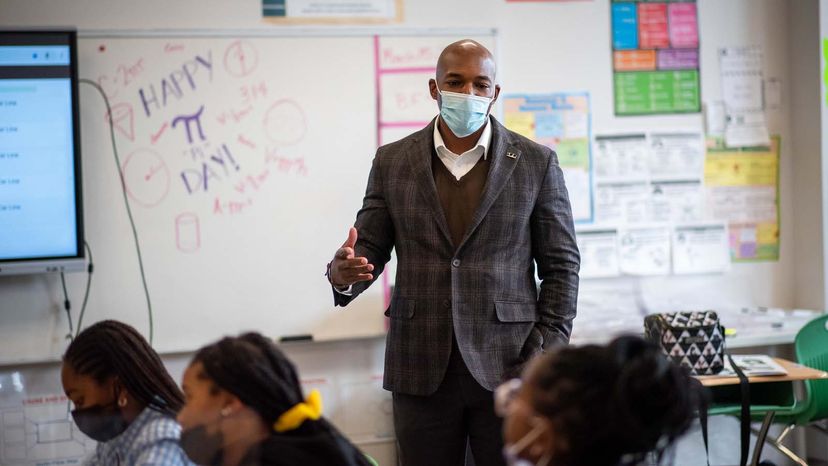

"African American youth are 20 times more likely than their peers to die from gun violence," says Joshua Byrd, vice president of Hawque Protection Group and criminal justice professor at American InterContinental University, both in Atlanta. "Gun violence is at an all-time high in Atlanta."

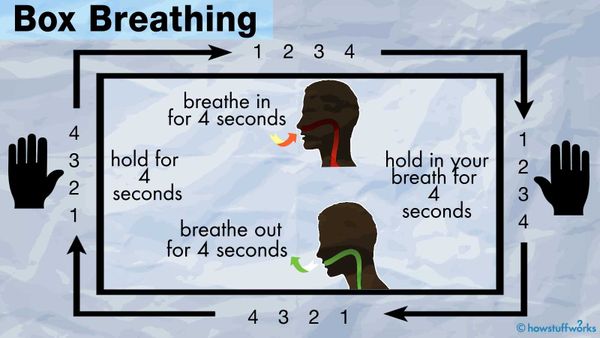

Byrd also is the committee chair of 100 Black Men of Atlanta, a nonprofit mentoring and education organization that recently launched the Anti-Gun Violence Committee. It's a public awareness project aimed at teaching de-escalation strategies to young people in Atlanta's most at-risk communities.

"What I teach the kids is that you want to survive and you want to make it home," says Byrd, who grew up in some of those same hard-hit Atlanta neighborhoods. "I often tell them, 'Winning a fight is actually losing your life.' You might win the verbal argument, but a lot of folks don't take that well, and gun violence is the next step."

Advertisement