In May 2006, two children in Texas helped stop a four-man home invasion in progress in their own home. That same month, a four-year-old boy helped save his mother's life when she started having an epileptic seizure, and a two-year-old beagle called for help when her person succumbed to a diabetic seizure - all by dialing nine, one and one on a telephone keypad (in the Beagle's case, she only pushed speed-dial number "9" and left the phone off the hook). These types of cases are an everyday occurrence at any 9-1-1 Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP) in the United States. Okay, the beagle thing was pretty rare, but still not unheard of.

As of 2006, 99 percent of the U.S. population has 9-1-1 service. There are 200 million 9-1-1 calls per year in the United States, and 9-1-1 call-takers encounter a mind-boggling array of emergencies in their line of work. They must be prepared for almost anything. One operator in Florida picked up a call from a man who was in the process of choking. The call-taker walked the man through the process of performing the Heimlich maneuver on himself using the back of a chair, dealing with the situation in an incredibly calm, encouraging manner considering the circumstances. She told him, after one failed Heimlich attempt, "I want you to try to thrust upward right under your belly button. Can you do that? Come on, sweetie, try it for me." The man dislodged a piece of chicken and was able to breathe again before the dispatched firefighters made it to his house.

Advertisement

The idea behind 9-1-1 is pretty simple: Give people a single, easy-to-remember number to call to receive help during any life-threatening situation. There is no national 9-1-1 system. The answering points and corresponding dispatch services are set up and maintained locally, usually by county, often in a joint effort between local government and any phone companies active in the area. You pay for 9-1-1 with your local taxes and through a surcharge on your phone bill.

In order to be effective, any emergency system needs to do three basic things:

- recognize when someone dials the emergency number on any phone (even a pay phone when no coins have been supplied)

- route the call to the nearest answering point based on the call's originating location

- notify the appropriate agency as quickly as possible so it can respond to the emergency

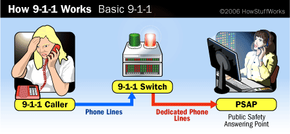

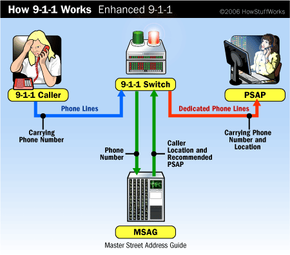

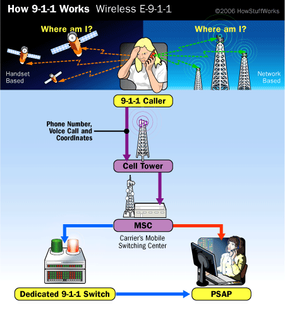

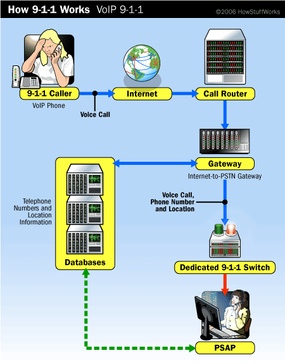

This is all that happens in basic 9-1-1 service. In enhanced 9-1-1 service, the answering point's equipment also automatically displays the caller's name and location, making step three above faster and more reliable. Enhanced 9-1-1 (E911) is not the same thing as wireless 9-1-1, but wireless 9-1-1 does require E911 improvements to be in place in order to work. The 9-1-1 system, which has always been based on the public switched telephone network (PSTN) that most of us use every day, has to adapt to constantly evolving technology, including the proliferation of cell phones, VoIP, and the introduction of safety measures like in-vehicle crash notification systems. Cell phones in particular have posed some big challenges to 9-1-1, and we'll get into that a bit later. For now, we'll focus on the 9-1-1 system in use when you dial out from a landline, which is still (but just barely) the most common way that people access a 9-1-1 answering point.

The phone lines in use when you dial 9-1-1 are sometimes dedicated lines and switches intended to provide some additional security from outages and congestion, but they're still just regular phone lines. The PSTN system routes 9-1-1 calls to the Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP) nearest to where the call originated. The operator at the PSAP gathers information about the emergency and alerts the proper agency - the police, the fire department or emergency medical services (EMS), or sometimes all three.

In the next section, we'll take a look at what goes on behind the scenes to make all of this work as smoothly as possible.

Advertisement