According to Richard Brecht, Deputy Director of the National Foreign Language Center, Japanese is the hardest language for a native English speaker to learn [source: Johns Hopkins]. But some people seem to have trouble learning any new language, to the point that a required language class in high school or college has been the academic downfall of many a student. There are others, however, who can pick up languages so easily that we say they have a special gift, a so-called "ear for languages." Can anything account for the difference?

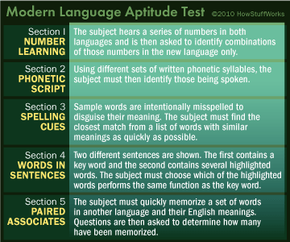

Linguists have studied whether certain people have a special aptitude for language acquisition. In the 1950s, psychologist John B. Carroll developed the Modern Language Aptitude Test to predict whether a person will be successful at learning a new language. The test measures the ability to perceive certain sounds, to recognize or infer grammatical rules, and the ability to maintain associations between words and their meanings. If someone scored well on the test at a young age, he or she may have been placed in an advanced classroom, but the test was also used to test government employees for overseas positions. In the 1960s, Paul Pimsleur developed his own test, which took into account a student's grade point average and attitude toward learning a new language as a means to predict success.

Advertisement

In recent decades, linguists have proposed that these tests could be used to sniff out students suffering from a "foreign language learning disability" -- that is, an inability to learn foreign language despite good performances in other courses. Professor Richard L. Sparks, who was the first to use the term, spent years researching the possibility of this disability. One study, for example, attempted to uncover whether students with poor foreign language skills had trouble in their native language, while another study tried to determine which came first: a lack of motivation for the language, or trouble learning the language.

In 2006, Sparks published an article in the Journal of Learning Disabilities calling his use of the term "foreign language learning disability" premature, as there was no definitive support that certain students were universally better or worse at learning languages than others. He also pointed out that the aptitude tests aren't very good indicators at predicting or diagnosing such a disability, and he's not the only one to criticize the tests in recent years. In other words, predicting language aptitude, or explaining why some people have it and some people don't, is no further along than it was a few decades ago.

Still, the very question of who has aptitude and who doesn't may get to the heart of the divide. If you approach a subject thinking that you're not very good at it, you may not work as hard to master it. So approaching a foreign language with the sense that it's hard may affect your ability to learn it. The attitude with which you approach the language is important, so if you can't stand Chinese food, that may influence your performance in Mandarin class. On the other hand, if you're motivated to learn Mandarin so that you can speak to your grandmother in her native tongue, you may find that you have an easier time picking it up. And immersion is also important -- if you wake up in China one morning and need to get around by yourself, you may pick it up very quickly indeed. Teachers say that with enough hard work, motivation and practice, those who may not think they're good at foreign language may end up being star pupils.

Advertisement