"Well-built men, 18-30, who would like to be eaten by me" was the typical advertisement Armin Meiwes took out on personals Web sites [source: Harper's]. After hundreds of false starts, he found a willing partner in 43-year-old Bernd-Jurgen Brandes. The two men met on March 9, 2001. It would be an odd night for both of them.

With Brandes high on painkillers and schnapps, yet consenting, Meiwes removed the man's penis with a knife. He flambéed it, and the two ate it together. Bleeding heavily, Brandes took a bath. He eventually lost consciousness, whereupon Meiwes slit his throat, butchered him and ate a little more of the man's flesh. Over the course of the next few months, Meiwes consumed 44 pounds of Brandes' dead body [source: Speigel].

Advertisement

The cannibal was eventually arrested and tried amid a media frenzy. But at the time of Meiwes' prosecution, Germany, like some other Western nations, had no law prohibiting cannibalism. Instead, Meiwes and other cannibals like him, including serial murderers Albert Fish and Jeffrey Dahmer, was convicted of the killing, not the eating. Murder is illegal; cannibalism exists beyond the law. It is taboo.

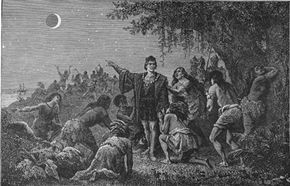

Cannibalism is as old as civilization, and likely older. The Kemites believed that Osiris their god of agriculture, gifted them with crops to prevent them from cannibalism. Greek mythology contains myriad tales of cannibalism, beginning with Chronos, the father of all gods. The Hebrews wandering the African desert resort to cannibalism in the Old Testament [source: Lukaschek].

Cannibalism is ancient, and yet -- as Meiwes, Dahmer, Fish and others remind us -- it's modern as well. It could be latent in every one of us: Recent events show that when the chips are down, even the most civilized humans will resort to cannibalism to survive. Yet, we recoil from the thought of others consuming human flesh and refrain from exploring the possibility of our own ability to cannibalize others.

But cannibalism was a part of life and death for cultures around the world. Those that gave it up as a practice did so unwillingly. And if history is any indicator, an end to cannibalism has not come. As Ted Turner predicted, in the face of climate change, those left to survive will resort to cannibalism [source: AJC]. Turner isn't an authority on the subject of anthropophagy (the clinical term for cannibalism), but he may not be far off. People have shown that we will eat one another in times of strife.

Advertisement