George and Jennie — like many of their Fayetteville neighbors — had both emigrated from Italy as children. The Sodders owned a trucking company and hauled coal from the region's mines. On the night of the fire, they were at home with nine of their 10 children (the second-eldest, Joe, was away with the Army, serving in World War II). George and the two oldest boys were already in bed. Jennie took the youngest, two-year-old Sylvia, to bed with her around 10 p.m.

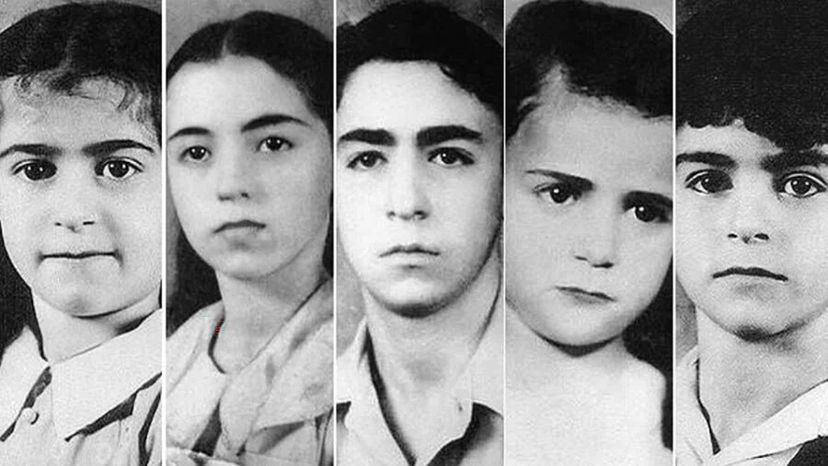

At 19, Marion was the oldest Sodder daughter. She and five of the younger children — Maurice, Martha, Louis, Jennie and Betty — stayed up a bit later. At 12:30 a.m., a phone call roused Jennie, the mother, who went downstairs to answer it. She told the caller, a woman with a "weird laugh," that she had the wrong number. Then she hung up and went back up to bed, noticing on her way that Marion had fallen asleep on the couch.

An hour later, Jennie Sodder woke again, this time to the smell of smoke. She rushed into George's office, which was full of flames. She and George carried Sylvia out of the house, and the three oldest children — John, Marion and George Jr. — escaped too. The stairs to the attic, where the younger children slept and where the family assumed they were trapped, were already engulfed in fire.

The Sodder's phone didn't work, so Marion ran to a neighbor's house where she tried to call the local fire department. Meanwhile, George tried frantically to reach the attic from outside the house. He rushed for a ladder that was usually stored against the side of the house, but it was missing. He tried to pull one of his coal-hauling trucks to the house so he could climb on top of it and reach the second story. Neither would start, though they'd just been driven the day before.

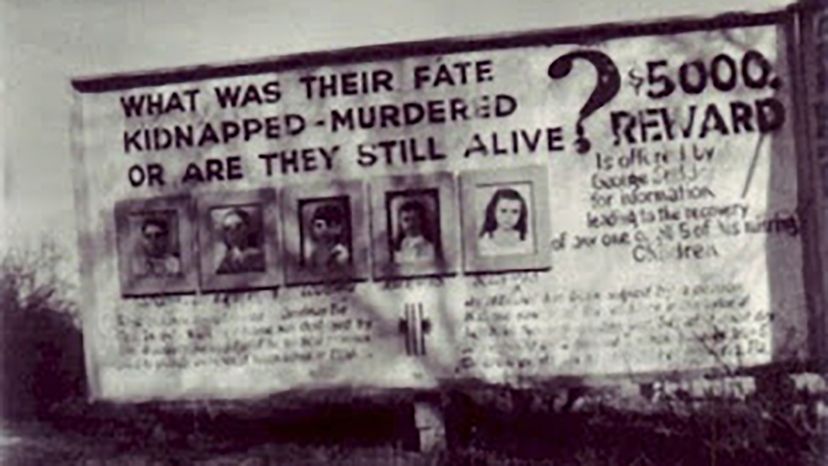

In the end, all the surviving Sodders could do was watch helplessly as their house burned and collapsed. When the fire department finally arrived hours later, there was nothing left but embers and ash. Everyone assumed the five young Sodders were dead.