We're not supposed to talk about this. The first rule of any fight club is, after all, you don't talk about fight club. We here at HowStuffWorks have big mouths, though, and don't really like to fight. So here goes.

In the 1996 Chuck Palahniuk novel, "Fight Club," and 1999 movie based on the book, two men inadvertently establish an underground network of clubs where men beat the tar out of one another. There's no good reason behind the fights other than fighting is reason in itself. Through these fights, the characters attempt to regain control of what they see as their increasingly emasculated lives. Rather than order furniture from catalogs or contemplate duvets, they choose to drop out of society and reinstitute their manhood through violence. This radical mentality attracts a multitude of other characters in the story that join the underground fight clubs which quickly spring up around the country.

Advertisement

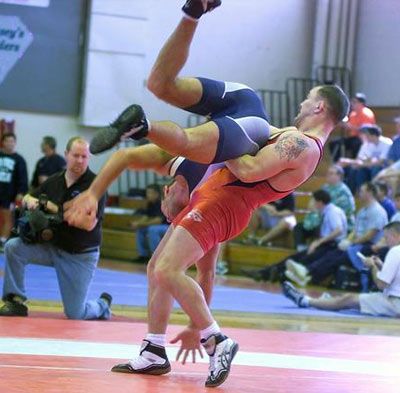

There's something visceral and exceedingly base that's derived from the sensation of knuckle impacting orbital socket. At least, that's what the main characters in the story decide. Fighting runs in stark contradiction to the norms of civilized society. Two people consentingly engaging in violence against one another is a different story, however. This, too, undermines society, but in a different way. As the two main characters in the story learn, it leads to anarchy.

It ultimately ends well for the protagonist (and badly for a few credit reporting companies). The story is, of course, entirely fictitious: Palahniuk says that he made the idea of fight clubs up [source: DVD Talk]. But following the release of the book -- and even more after the movie's release -- the author stood accused of inadvertently creating a real-life fight club trend.

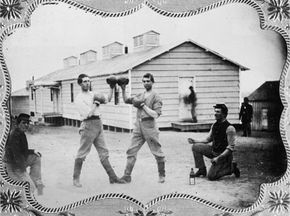

So are there real-life fight clubs? Before we get to that, find out about violence through the ages on the next page.

Advertisement